In search of Sherlock Holmes

“Elementary, my dear Watson!”

I was on a train in the Bernese Oberland, a German speaking part of Switzerland, and the words were English, and yet they didn’t feel out of place. Because I too was on a pilgrimage in search of Sherlock Holmes.

In the public consciousness, Sherlock Holmes is most closely associated with two places:

- 221B Baker Street

- The Reichenbach Falls

And in 2016 I was able to visit both those places.

Baker Street

221B Baker Street has been a part of the Sherlock Holmes legend from the very beginning.

Dr Watson was recently back from service in Afghanistan and looking for someone to share a flat with to reduce expenses. A friend introduced him to Sherlock Holmes, who had his eye on a place in Baker Street:

We met next day as he had arranged, and inspected the rooms at No. 221B Baker Street, of which he had spoken at our meeting. They consisted of a couple of comfortable bed-rooms and a single large airy sitting-room, cheerfully furnished, and illuminated by two broad windows. So desirable in every way were the apartments, and so moderate did the terms seem when divided between us, that the bargain was concluded upon the spot, and we at once entered into possession.

It became the consulting detective’s headquarters, with a particularly important role when Arthur Conan Doyle moved into short stories. It was there that Holmes received potential clients (and surprised them with his powers of deduction). It was there that he summed up cases. And, in between, he might use it to play the violin, smoke a pipe, confer with Scotland Yard detectives, disguise himself, or just generally come and go at extremely odd hours.

Though later adaptations have used and sometimes updated 221B, it was traditionally set in Victorian London at the time of gas lamps, hansom cabs, and Empire. The British Empire was then near its peak, so it’s not surprising that some of Holmes’ cases involve an Australian bushranger, a Canadian farmer, and soldiers in India at the time of the 1857 mutiny (though he does also have notable clients from Europe).

A modern day museum

London is a different place now. It’s still a large and important and historical city, but it’s no longer the centre of an empire. Though of course that memory of empire still affects how many British people see themselves, and I think contributed to Brexit and the visions many have of a post-Brexit world where Britain is once more a power.

But it’s also a tourist city with many museums, and one of them just happens to be a Sherlock Holmes museum:

As it happens, this museum isn’t “really” 221 - it used to be 239 Baker Street. Abbey House, for many years the headquarters of the Abbey Road Building Society, was at 215 - 229 Baker Street, and the building society actually had a “secretary to Sherlock Holmes” on staff dealing with the considerable fan mail addressed to 221B. However, after much dispute the museum ended up getting the number, and I suppose the fan mail with it.

I’ve never actually been in to the museum - there’s far too much to see in London, and museums can have such inconvenient opening times. However, I passed it late one summer evening on my way back from a busy day and stopped to admire it.

It wasn’t just the museum, either. Next door was Hudson’s Old English Restaurant:

And over the road road was the Holmes Grill:

This actually turned out to serve Lebanese food, which was interesting (I’ve got nothing against it, but it’s not exactly the first cuisine I’d associate with the Great Detective).

The detective must die

After a while, Doyle got sick of Sherlock Holmes. The stories were too formulaic, and he wanted to be known for his historical fiction (which is mostly less well known, though some is certainly good).

And so he resolved to kill him off. When he was in Switzerland, his host suggested that the Reichenbach Falls might be a good place to get rid of him. Doyle was impressed, as he showed in that final story:

It is indeed, a fearful place. The torrent, swollen by the melting snow, plunges into a tremendous abyss, from which the spray rolls up like the smoke from a burning house. The shaft into which the river hurls itself is an immense chasm, lined by glistening coal-black rock, and narrowing into a creaming, boiling pit of incalculable depth, which brims over and shoots the stream onward over its jagged lip. The long sweep of green water roaring forever down, and the thick flickering curtain of spray hissing forever upward, turn a man giddy with their constant whirl and clamour. We stood near the edge peering down at the gleam of the breaking water far below us against the black rocks, and listening to the half-human shout which came booming up with the spray out of the abyss.

And the resulting account - The Adventure of the Final Problem - is one of my favourite Holmes stories.

To give meaning to the great detective’s death, Doyle pits him against the “Napoleon of Crime”: Professor Moriarty, an intellectual super-villain who - strangely - had never even been hinted at beforehand. Escaping from London, Holmes and Watson wander through the valleys and passes of Switzerland heading for Meiringen. Here, Doyle is happy for the detective to foreshadow his coming death:

“I think that I may go so far as to say, Watson, that I have not lived wholly in vain,” he remarked. “If my record were closed to-night I could still survey it with equanimity. The air of London is the sweeter for my presence. In over a thousand cases I am not aware that I have ever used my powers upon the wrong side. Of late I have been tempted to look into the problems furnished by nature rather than those more superficial ones for which our artificial state of society is responsible. Your memoirs will draw to an end, Watson, upon the day that I crown my career by the capture or extinction of the most dangerous and capable criminal in Europe.”

And it’s very neat, really. Moriarty and Holmes die together, and their bodies are never recovered from the falls:

A few words may suffice to tell the little that remains. An examination by experts leaves little doubt that a personal contest between the two men ended, as it could hardly fail to end in such a situation, in their reeling over, locked in each other’s arms. Any attempt at recovering the bodies was absolutely hopeless, and there, deep down in that dreadful cauldron of swirling water and seething foam, will lie for all time the most dangerous criminal and the foremost champion of the law of their generation.

And that leaves nothing but Watson’s heart-broken tribute to “him whom I shall ever regard as the best and the wisest man whom I have ever known”.

For the record, some years later Doyle revived Holmes, mostly I gather because he needed money and realised he was paid for more for Holmes stories than for other stories.

Moriarty remained dead and Doyle hardly used him, but he has taken a much larger role in later stories, plays, and TV adaptations (just as one example, he has attempted to steal the Crown Jewels in both the Rathbone era and the Cummerbatch era).

A visit to Switzerland

In 2016, I spent most of my overseas time in the UK. But near the end I got the chance to spend 1.5 weeks in Switzerland, and I particularly wanted to discover the mountains.

However, I really didn’t know that much about Switzerland (other than, of course, that the Alps were likely to contain many beautiful snow-capped peaks). The Reichenbach Falls was one of the few places I’d actually heard of before I arrived in Switzerland.

When I discovered the falls were near Grindelwald - a place I’d heard of from friends and planned to visit - it made complete sense for me to visit them. That led me from Bern to Meiringen, and it was while on the train approaching Meiringen (possibly while we could actually see the falls out the window) that I heard my fellow passenger saying “Elementary, my dear Watson!”

Meiringen gained an honorary citizen

To be clear, I’m sure Meiringen was a nice place and the Reichenbach Falls an impressive waterfall long before Doyle placed Holmes there (otherwise he would have chosen somewhere else). But being featured in such a well-known story has put both of them on the map, and it’s also changed both of them. I think it’s fair to say that this village and these falls, while retaining their Swiss-German character, have also become a little fragment of England.

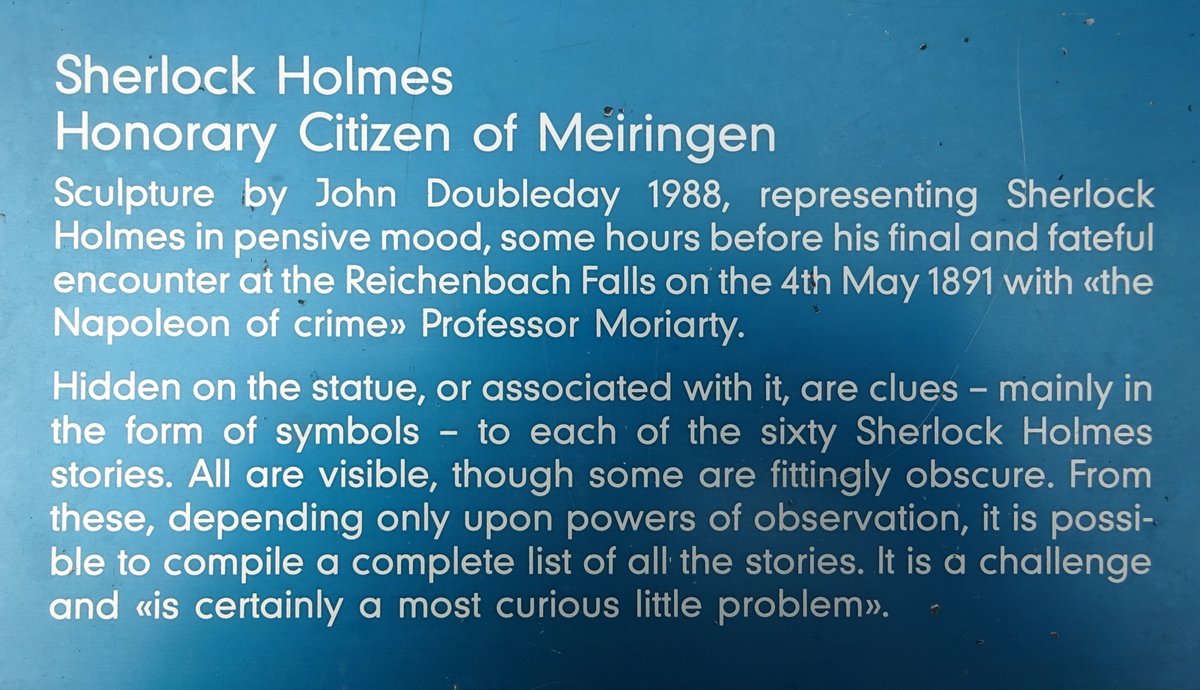

For that reason, it’s fitting that Sherlock Holmes is sculpted as an honorary citizen:

That statue is actually outside another Sherlock Holmes Museum (as at Baker Street, the timing didn’t suit, so I didn’t go in):

There’s a Sherlock Club, which has a Sherlock Lounge:

In addition, there’s a Sherlock Hotel, an Arthur Conan Doyle Place, and probably many more Holmes links that I didn’t pay attention to.

However, all that is just a precursor to the falls themselves.

The Reichenbach Falls

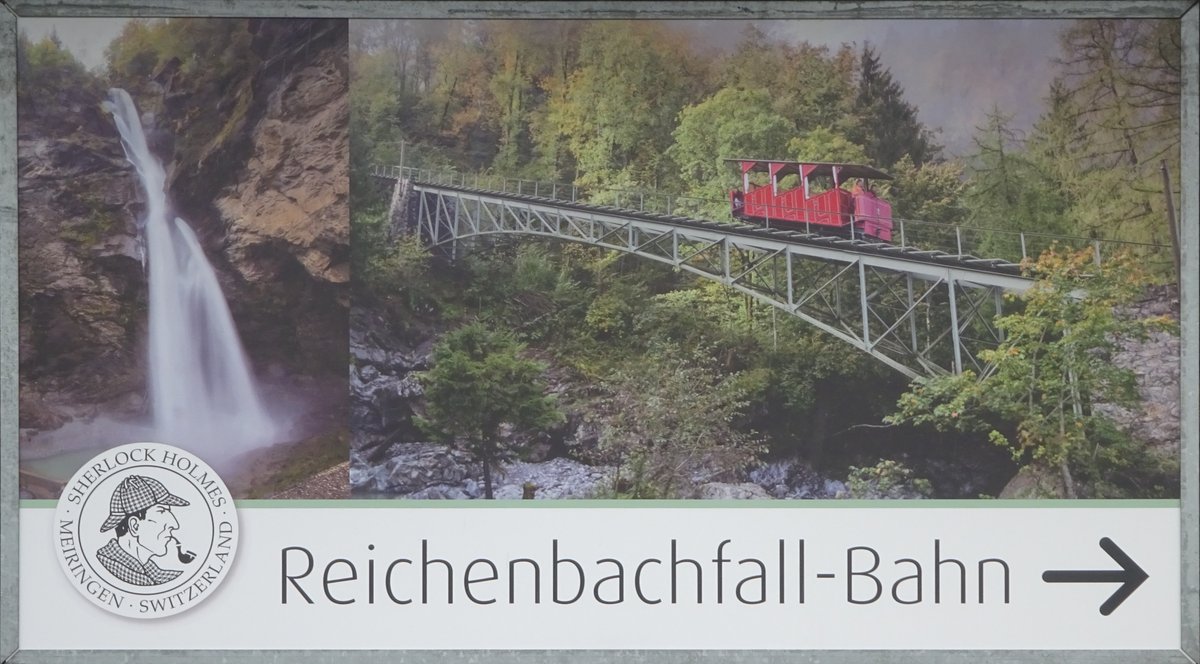

There’s now a funicular up to the falls, which it seems was added not long after Doyle was there. Note the Sherlock Holmes badge in the bottom left.

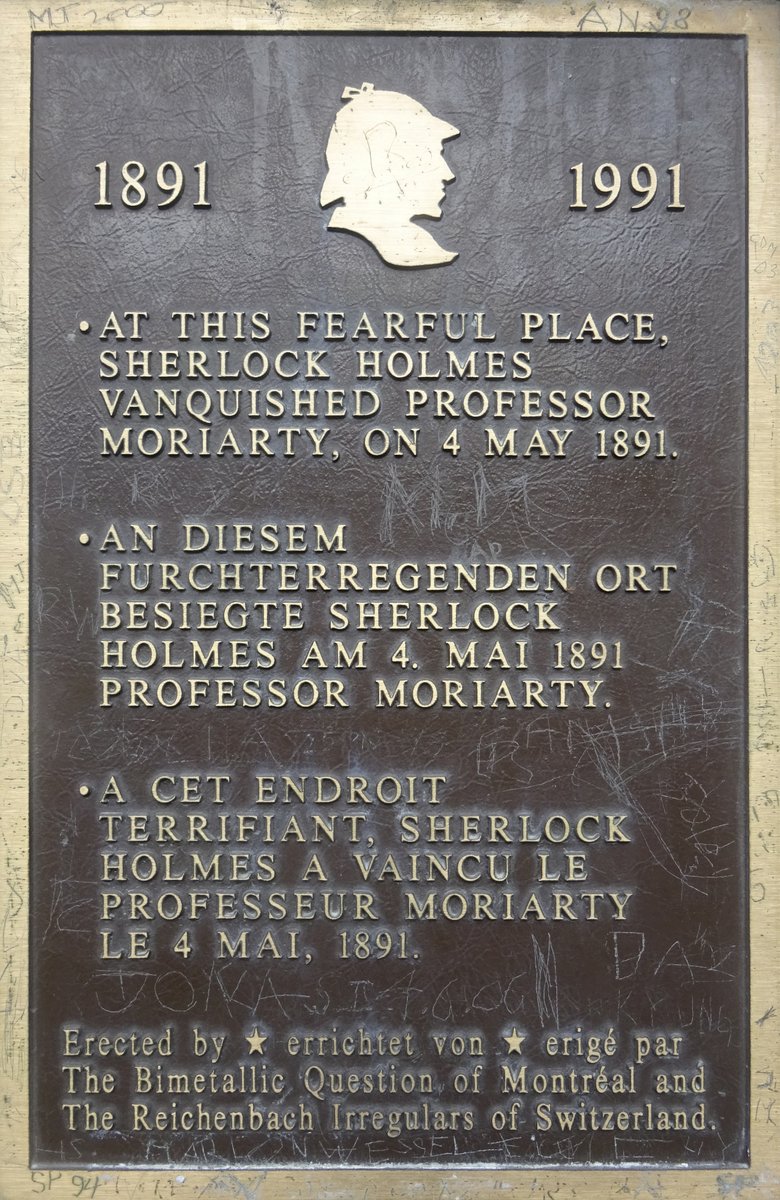

And the commemorative plaque:

Being me, I decided to walk up, as Holmes and Watson had, in spite of the rain that was threatening and did actually catch me:

When I came to the same narrow ledge that Moriarty and Holmes had struggled on, there was another commemorative plaque:

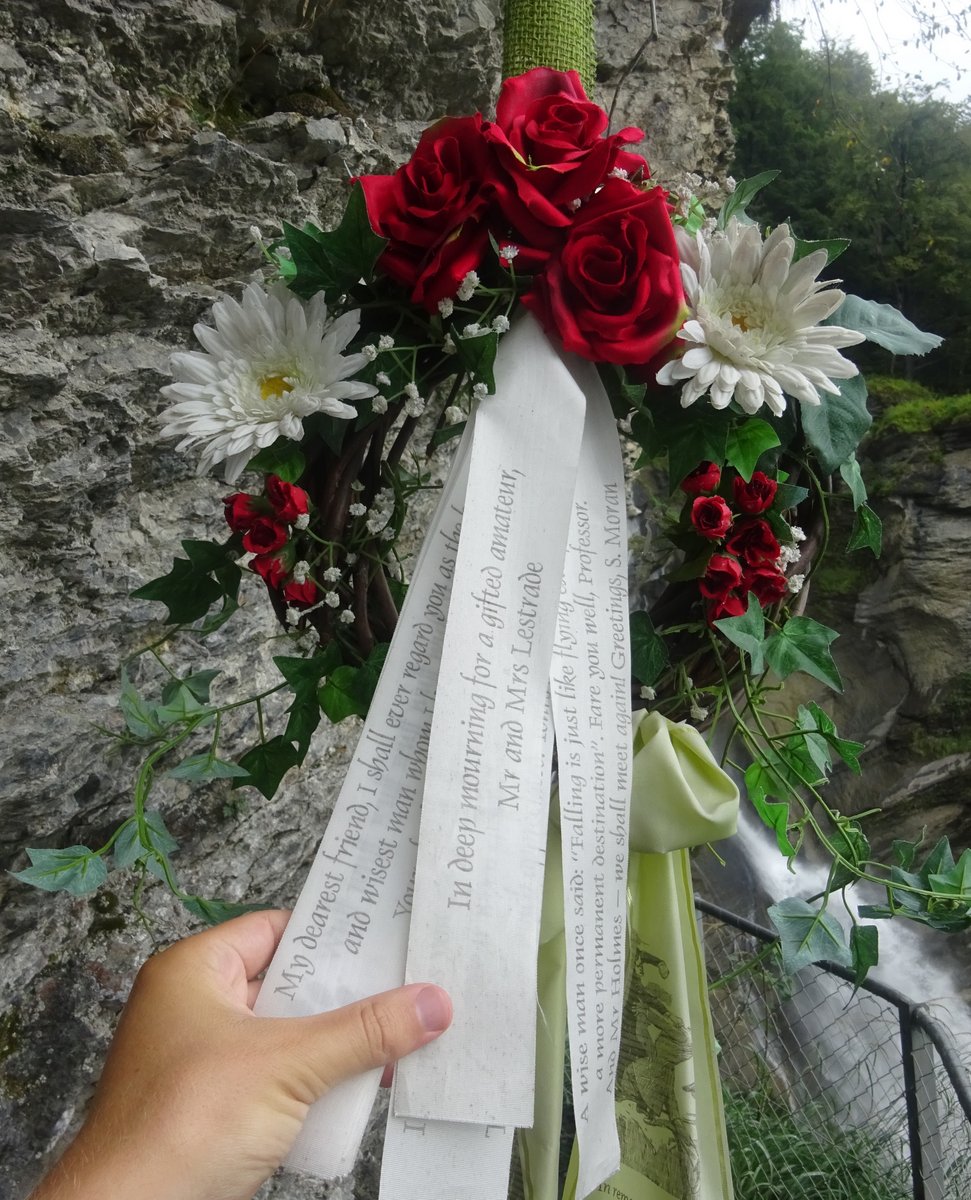

And I could hardly stop laughing when I got to the tributes from such luminaries as John Watson, Mr and Mrs Lestrade, Martha Hudson, S Moran, and Toby the dog:

Note in the background the modern convenience of a safety fence - had that been there in Doyle’s day, he might have had to find some other place to kill off his detective.

The ledge is on the other side of the falls from the funicular top station, but it’s possible to get across, and over there you can even impersonate the great detective:

Is it really the same?

I had re-read The Final Problem on the train that morning. And that left me with a nagging feeling that the falls weren’t quite as I imagined them. They were certainly impressive, and the ledge did seem narrow enough that a struggle would be unwise and might lead to a fall if there was no safety fence. But the waterfall was nowhere near as close to the ledge as I’d imagined:

And it was only when writing this post (yes, five years later) that I found out why: 125 years is a long time and water is powerful stuff, so the falls have actually retreated. According to the infallible Wikipedia:

The pathway on which the duel between Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty occurs ends some hundred metres away from the falls. When Doyle viewed the falls, the path ended very close to the falls, close enough to touch it, yet over the hundred years after his visit, the pathway has become unsafe and slowly eroded away, and the falls have receded further back into the gorge.

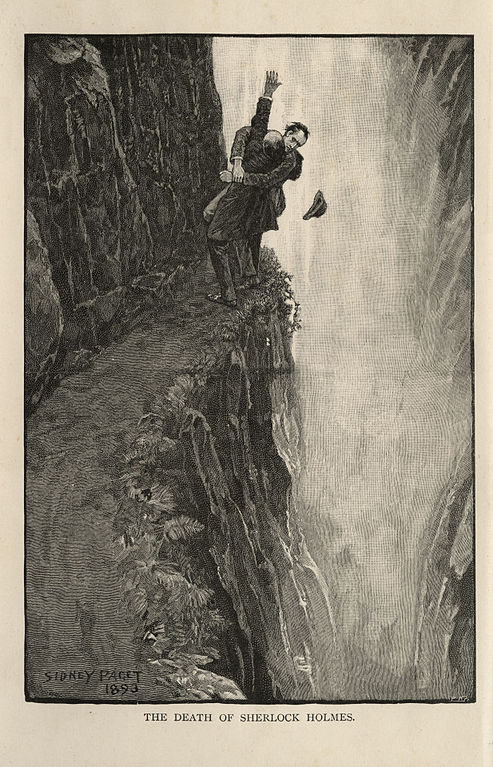

I guess this matches the original Sidney Paget illustration:

Doyle’s words left a vivid impression on me as a teen, and I’d love to have seen it as it was then. However, I love waterfalls, and it’s still pretty impressive how it is now.

I was glad to get the chance to visit it both from the “Sherlock enthusiast” perspective and the “waterfall enthusiast” perspective. And at least I didn’t have to go to the trouble of visiting in full Victorian dress, like the London Sherlock Holmes Society apparently does.

Walking on

It was hard to tear myself away from the falls. I was due to be in Grindelwald that night, and had thought of walking there, but it would have been another 20 km and I really hadn’t left enough time. My compromise plan was to walk as far as Rosenlaui (the destination Holmes and Watson were aiming for that day) and then catch the last bus on to Grindelwald. However, once it began raining heavily again I stopped at an earlier bus stop and got a hot chocolate while waiting for the bus.

And, as far as I was concerned, that was the end of The Adventure of the Reichenbach Falls, though only really the start of The Adventure of the Swiss Alps.

Back home

In the 130 years since that premature death, Sherlock Holmes has remained popular, and has been revived and re-worked in far more ways than most characters. The two Holmes museums I saw on my travels are only a few of the many clubs, museums, and other venues dedicated to the great detective. I do recommend The Life & Death of Sherlock Holmes (one of my favourite books for 2019) for a detailed discussion of the many ways Sherlock Holmes has both continued and changed over the years.

There have been two Holmes plays at my local theatre in the last few years: Baskerville, and Sherlock Holmes and the Suicide Club. Both have been enjoyable, though very different from each other and from the original Doyle stories.

But we also have a pub named after him:

As it happened, the first time I walked past it was the evening I had the MSO’s very British Last Night of the Proms. So it felt fitting eating at a pub with a Union Jack out front. The food was decent and some of the decorations good, but it’s not a part of Melbourne I visit often, so I haven’t been back.

How things change

Sherlock Holmes isn’t the only fiction where I’ve visited related places when I’ve got the chance. In the days after the Reichenbach Falls I saw places in the Swiss Alps that it turned out had inspired some parts of Tolkien’s Middle Earth. I’ve also seen places near Birmingham from his childhood that are said to have inspired him. When in London, I’ve visited many of the places mentioned by Charles Dickens. I’ve seen places from Kidnapped in Scotland, Winnie-the-Pooh’s enchanted places in Ashdown Forest, Harry Potter locations, and probably a bunch of others.

But one common thing I’ve noticed is that the places may be similar, but they’re not the same. It’s still interesting to visit them, of course, but you’re not going to see exactly what the author saw or imagined.

Sometimes that will just be from changes over time, like I found with the falls. Similarly with Baker Street - the museum may well capture some of the atmosphere of Victorian times, but the city has moved on and changed.

Sometimes it’s a direct result of the fiction’s success - without the fiction there wouldn’t be a 221B Baker Street, and the falls would remain spectacular, but wouldn’t have the Sherlock Holmes plaques and tributes and so forth that drew me to it and added another layer to my appreciation of it.

Time to return?

Maybe if I ever returned to London I’d make the Sherlock Holmes Museum one of my stops. But I’m not sure I ever will.

I’d been hoping to revisit the Reichenbach Falls as part of a multi-day walk through the Swiss Alps last year (with 20:20 hindsight, it’s easy to say things didn’t go as planned). Now I don’t know whether I will ever end up returning there. I’m not sure I’d go there except as part of some larger goal, but if I did happen to be in the area I’d certainly like to return.

But if you haven’t been there, I really enjoyed it and think it well worth a visit. The waterfall alone would make it worth visiting, and the Sherlock Holmes connection means there’s now so much more to it. It was a fitting place for Doyle to kill off his famous detective.

RIP Professor Moriarty.

May Sherlock Holmes live long and prosper and continue to evolve!