Leaf by Niggle: Discovering the mountains

In my last post, I talked about how an Edinburgh Fringe event changed my view of Leaf by Niggle. As a story, it relied on the eternal life I had rejected, and left me feeling that I really didn’t know what came next.

However, the next day I flew to Switzerland for a short visit, and I was looking forward to discovering a little of the Alps. Little did I know that that visit would give me a new insight into Leaf by Niggle and into J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth. It would also do a lot to ease the ache of loss of eternal life.

The key quote

Back in Edinburgh, there had been one quote that particularly intrigued me:

He was going to learn about sheep, and the high pasturages, and look at a wider sky, and walk ever further and further towards the Mountains, always uphill. Beyond that I cannot guess what became of him. Even little Niggle in his old home could glimpse the Mountains far away, and they got into the borders of his picture; but what they are really like, and what lies beyond them, only those can say who have climbed them.

After the performance, I talked with Richard Medrington, the writer/actor. And one thing I asked particularly was “What do you think Tolkien meant about the mountains?” He didn’t really have an answer.

For me, I’d just come from the Cheviots at the end of the Pennine Way. They’d had nice rolling hills, but it was nothing like that description. The area around Scafell Pike had been wilder, but it didn’t come to mind. And there hadn’t been any snow on it, anyway.

Mont Saleve - Discovering the mountains

From Edinburgh I flew to Geneva, then briefly crossed into France to climb Mont Saleve.

Up on the plateau, there were supposed to be views out to the Mont Blanc massif. Since I knew Mont Blanc was the highest mountain in the EU, I thought it was worth a look. It was in the distance, so my photos didn’t come out that well, but I found it utterly breath-taking. At the time I was taking audio notes of my experiences, and I rhapsodised over the view.

The mountains were tall and dramatic and bare. Tolkien had talked about the mountains going ever upwards, and this view looked like that. It was what I felt it might be like wandering the Himalayas.

It also had the pastoral elements Tolkien described, since I heard the enchanting notes of a cow bell orchestra for the first time.

Grindelwald - Among the mountains

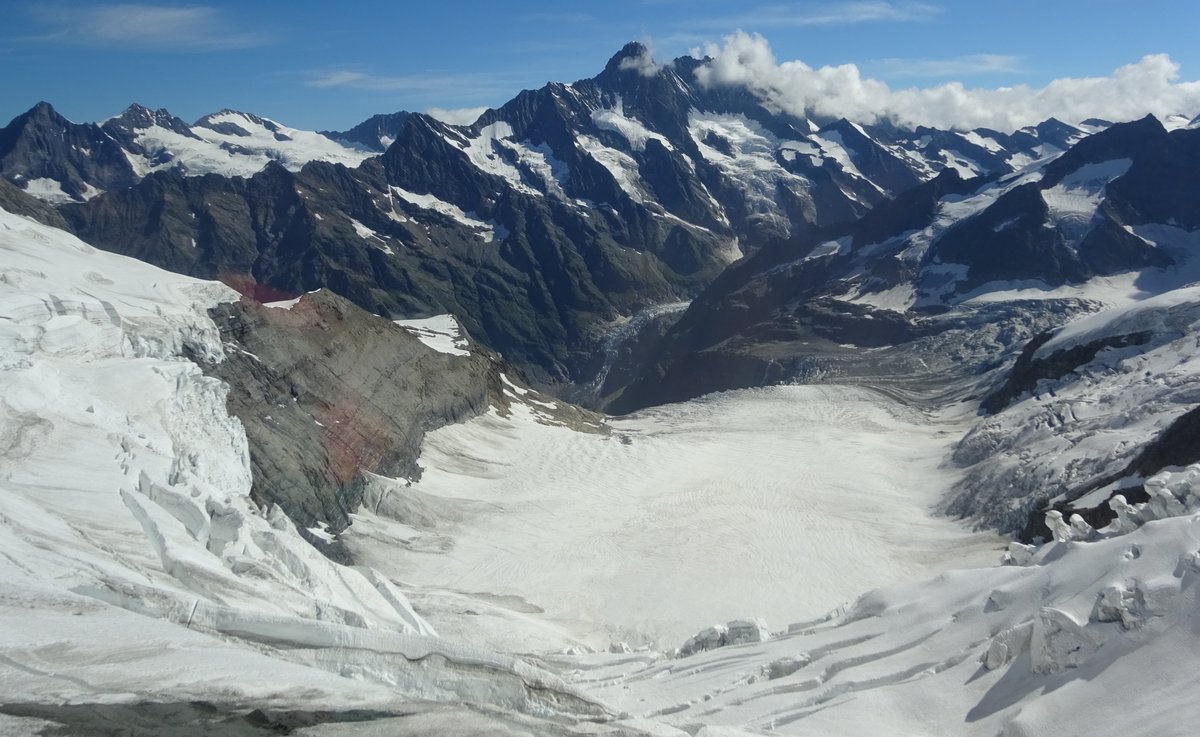

A few days later I found myself at Grindelwald. Here it wasn’t just seeing the mountains at a distance: I was in among them. I could eat breakfast with views of Jungfrau:

I could see peaks reflected in mountain lakes:

I could take a train to the highest station in Europe and see glaciers and ice-fields and snow-capped peaks, and even walk in the snow among those peaks.

It was wonderful.

Lauterbrunnen - another Tolkien connection

From Grindelwald I travelled to Lauterbrunnen to see waterfalls. Originally, I had intended to go the long way by train. But then I remembered my Pennine Way experience, and decided to walk there instead. Tolkien was far from my mind.

Lauterbrunnen turned out to be in a valley with high, near sheer cliffs on either side. But it wasn’t till that evening that I discovered that not only had Tolkien been there, but this location had been the inspiration for another well known deep valley with waterfalls. It was even in the name: Riven dell.

What I found was that Tolkien had actually travelled the same route as I had that day, but in reverse: Walking from Lauterbrunnen to Grindelwald.

As he wrote to his son Michael:

The hobbit’s journey from Rivendell to the other side of the Misty Mountains, including the glissade down the slithering stones into the pine woods, is based on my adventures in 1911.

It was cool to discover that Tolkien had been inspired by some of the same mountain vistas and valleys as I was admiring. In particular, we know they were an inspiration for the Misty Mountains in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

However, I imagine they were an inspiration for the mountains in Leaf by Niggle as well. Which means I was closer to the truth than I knew at Mont Saleve when I first thought “This is what Tolkien was talking about when he was talking about the mountains”.

Walking in that valley I covered more ground that Tolkien had walked, and even saw the high pasturage and the sheep grazing that Niggle was to discover:

The Battle of the Peak

In The Hobbit, they cross the Misty Mountains in summer, and don’t have to deal with snow. In The Lord of the Rings they attempt a crossing using the Redhorn Gate below Caradhras in winter. It doesn’t go well: They are trapped in the snow, turn back, and eventually have to find their way through Moria and meet a Balrog.

I think this peak that I saw is the Silberhorn:

In a 1968 letter (more than 50 years after visiting Switzerland), Tolkien identified this peak from a different angle as the inspiration for Zirakzigal (“silver spike”): the location of Gandalf’s final struggle with the Balrog. This struggle, to be precise:

Those that looked up from afar thought that the mountain was crowned with storm. Thunder they heard, and lightning, they said, smote upon Celebdil, and leaped back broken into tongues of fire. Is not that enough? A great smoke rose about us, vapour and steam. Ice fell like rain. I threw down my enemy, and he fell from the high place and broke the mountain-side where he smote it in his ruin.

I wasn’t looking for that Tolkien connection, but it’s still cool to discover it.

The tug of the mountains

A few days later I was in Zermatt, with the Matterhorn in view, climbing up to Gornergrat, then on to Hohtalli. I’d gained around 1,600m of elevation, it was two hours till dark, the mountains were already under cloud, and they were expecting heavy rain (which did catch me on the way down). I wasn’t equipped to go walking on the ice, and had probably already gone further than I should.

However, I still felt that tug to continue onwards and upwards. Like Niggle, I still wanted more.

In this case it wasn’t just about those particular mountains. I knew it was my last big walk. In 48 hours I’d be back in London. In a week I’d be back in Melbourne. Returning back to ordinary life, the same as I’d worried about in Edinburgh. But perhaps with a little more resolve and a little more purpose.

Comparing with The Last Battle

Leaf by Niggle was published over ten years before The Last Battle, and it’s likely C.S. Lewis would have known it from Inklings meetings even before it was published. Both Tolkien and Lewis talked about an afterlife too wonderful to describe, and both of them included high mountains as part of that afterlife.

As a result, I find it interesting that I initially felt the loss of eternal life much more from The Last Battle than from Leaf by Niggle, and that I noticed the mountains in Leaf by Niggle but didn’t notice them in The Last Battle. Though in this context I’m intrigued that Lewis is very specific that his mountains do not have snow, while Tolkien’s ones do.

To me, The Last Battle has far too much of an agenda: In particular, Lewis tries (and, I think, fails) to portray a false religion without exposing the problems with his “true” religion. Leaf by Niggle is shorter, and, while I still reject Tolkien’s worldview, I see much more of beauty and much more I agree with than in The Last Battle.

So, while re-reading The Last Battle was reconnecting with a past that I have come to terms with rejecting, Leaf by Niggle is still very much part of my present. I may have changed significantly, but the story has changed with me. Tolkien managed to get at the absurdity of life and the beauty of the mountains without triggering the same feelings of loss as Lewis did.

My mountains may not be as wondrous as Tolkien’s mountains, or as long-lasting as the mountains in Lewis’s “Aslan’s Country”, but they are mine. I don’t need to wait for some perfect afterlife: I can visit and admire them in this life.

Not an entirely new revelation

Hiking in the mountains was a part of my childhood, particularly visiting the Grampians as a family. In adulthood I fell in love with the Australian Alps, and earlier in 2016 had climbed Kosciuszko, our tallest peak. In Spring 2010 I’d seen snow-capped peaks in Zion and Yosemite, and in Summer 2014 I’d climbed a 14er in the Rockies and encountered permanent snow. Without that mountain climbing background I wouldn’t have climbed the UK Three Peaks or walked the Pennine Way.

However, the mountains in Switzerland still felt different. Perhaps they were taller and grander, but perhaps it was just that I was there at the right time for me. Discovering them helped me deal with the pain of loss that Leaf by Niggle had triggered. More, it gave Leaf by Niggle new meaning and allowed me to hold onto it as a favourite story. And it helped give me purpose after deconversion.

And that is a common thread in my deconversion journey: While it has taken me to completely unexpected places, it is often a continuation of the person I was already becoming. Things which felt like new and unexpected revelations actually turn out to be things I was preparing for for years. I just hadn’t noticed it yet.

What came next?

As I said last post, it was difficult in Edinburgh saying farewell to UK tourism. Saying farewell to Switzerland was even more of a wrench - but it also gave me something new to aim for.

I knew there were more snow-capped mountains to discover and explore, and I wanted to visit some of them. By the time I left Switzerland I had a short list of possibilities for my next overseas trip:

- Returning to Europe to explore more of the Alps.

- Visiting Nepal to explore the Himalayas.

- Finally visiting our near(ish) neighbour New Zealand.

At the time I thought I was more likely to remain in the Southern Hemisphere, and so it proved: Last February I visited New Zealand’s South Island and had a wonderful time. To glaciers and glacier fed streams and snow-capped peaks I added icebergs and fjords and alpine parrots and so much more. To Tolkien’s Misty Mountains inspiration I added the magnificent setting of the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit films. Hopefully I’ll be able to write about this soon, given I was supposed to be wrapping up my 2019 review before 2021.

However, I also thought it likely that the European Alps would lure me back, and so it proved. Before Covid-19 struck, this year was to be the year I returned to the Alps as part of a round the world trip. While I had many new places to see, I also intended to revisit Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen. Not so much because of the Tolkien connection as because of the lure of the mountains.

Mountains closer to home

In the years since returning from Switzerland, I’ve also spent time discovering mountains closer to home. Last week I discovered Mount Buller - a ski resort in winter, and a beautiful upward climb in summer:

Up there, the mountains stretched off into the distance in all directions:

Next week I plan to return to Kosciuszko.

I may not have seen the snow-capped peaks I wanted to this year, but there are still mountains about and they continue to lure me.

Why do we climb mountains?

The classic answer is of course “Because they’re there”. And to me that is a lot of it: They are there to discover and explore.

But I think there’s more to it: They can provide a challenge, which makes reaching the summit an achievement. There can be beautiful views, both along the way and at the top. And there’s nowhere quite like them.

They draw the painter, they draw the photographer, they draw the writer, and they draw the hiker. I may not be a painter like Niggle, but I am in some measure a photographer, a writer, and a hiker.

Photos allow me to share my experience with others (like in this post). As P.G. Wodehouse put it in his amusing William Tell Told Again:

Once upon a time, more years ago than anybody can remember, before the first hotel had been built or the first Englishman had taken a photograph of Mont Blanc and brought it home to be pasted in an album and shown after tea to his envious friends, Switzerland belonged to the Emperor of Austria, to do what he liked with.

I don’t share to make my readers envious, but to make them aware that these experiences exist. Mountain climbing is one of the things that gives my life meaning, and perhaps others can find the same.

Some day I will no longer be able to climb mountains. Perhaps then for a time I will still have photos and memories of past achievements, but one day those too will go.

The mountains will likely outlast me, but they too will change. They may be worn down. They may be covered with snow less frequently. Eventually they may vanish altogether, while other mountains grow.

There is no deep enduring meaning to the universe in me climbing the mountains, or in me recording what I find there. But there is meaning to me.

Mountain climbing in the presence of death

Because Niggle’s mountains are in the afterlife, I assume they are “safe” to climb. My mountains aren’t like that. Discovering and exploring them helps me find meaning in the face of death - but it also involves risk of death.

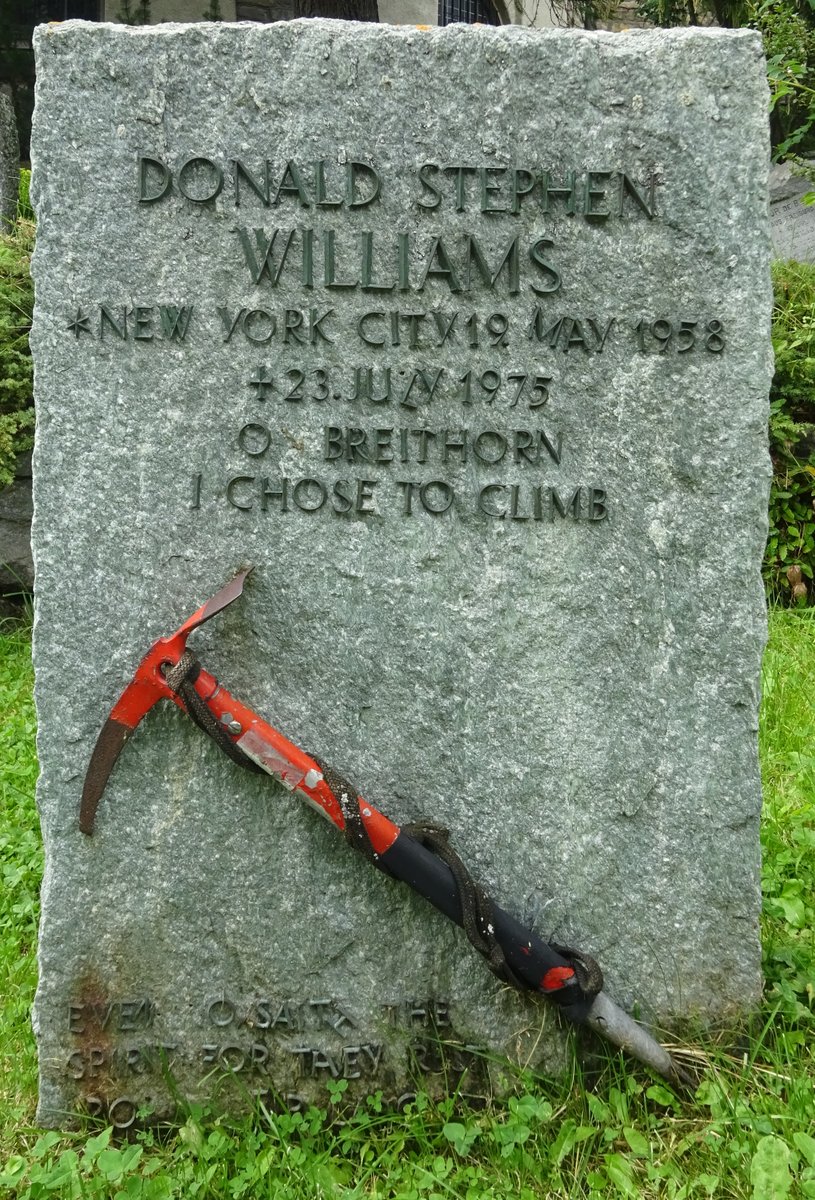

In both Switzerland and New Zealand I have seen cemeteries dedicated to mountain climbers who have lost their life climbing, many younger than me. The mountains are things of beauty, but they also have great power. Some climbers have been confronted by avalanches, by landslides, or by unexpected weather. Others have succumbed to an over-ambitious climb, to a chance slip, or to a frayed rope breaking.

Like any cemetery, some epitaphs had explicit references to an afterlife: “Who passed into fuller life from the Matterhorn, age 24”. Others didn’t: “Forever at rest in his beloved mountains”.

Some climbers are commemorated and celebrated by name. Others aren’t:

Tolkien was well aware of the dangers of the mountains: They aren’t safe in either The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. The passage of the Misty Mountains was dangerous, while the Lonely Mountain was tall and grim, and it was hard work for the dwarves to climb and explore.

In New Zealand I saw a quote from Sir Edmund Hillary: “I don’t think a climb is really worthwhile unless you have been scared out of your wits at least twice”. But that isn’t my approach. I can see the beauty and feel the tug of the mountains, but I know I’m a hiker, not a full-fledged mountain climber. I don’t have the skill or the experience for serious climbing, and I’m not sure that will change.

Even so, I make choices, and some of those choices involve risks. I try to stay within my skill level and minimise those risks, but nothing is risk free. Exploring the mountains gives me joy and peace and a measure of purpose. It may also cost me my life. And in the unlikely case it ever does, I think this epitaph would best capture my feelings:

Conclusion

So, to sum up: I left Scotland in unrest, due in part to a performance of Leaf by Niggle. I didn’t go to the Swiss Alps as a Tolkien fan - I didn’t even know he had been in Switzerland, let alone that it inspired parts of his tales.

But what I found there wasn’t just healing for wounds from overcoming indoctrination, but new purpose and hope and joy, and a new connection with Tolkien’s writings. And all this happened in little more than a week.

Clearly it was the right time and place to make that connection, to overcome my demons, and to gain new purpose.