The perils of incumbency

Last year when I was in Sydney, I visited the State Library of NSW, and they had a collection of Australian political cartoons from the last 120 years. Some of them were funny, while others would probably have been more funny if I actually understood their political context. But there was one from our last election that particularly caught my eye.

The cartoon

Here’s the cartoon:

It makes me laugh, but it’s also true. I was there for that election campaign, and that’s what it felt like.

Back then, I described some of the background in my pre-election post. Personally, I didn’t feel I knew much about Anthony Albanese and what he stood for, but to the electorate at large that didn’t seem to matter. After a disastrous 2019 campaign, where Labor had promised big changes (many of which I agreed with) and were rejected, in 2022 they were running a small target campaign. And it worked.

The Coalition had been in power for nine years (and three Prime Ministers…), and Prime Minister Scott Morrison had become particularly disliked. Expressions like “I don’t hold a hose” and “It’s not a race” had become part of the vernacular. So it wasn’t hard to imagine that an Albanese-led government would be better than more of the same from the Coalition.

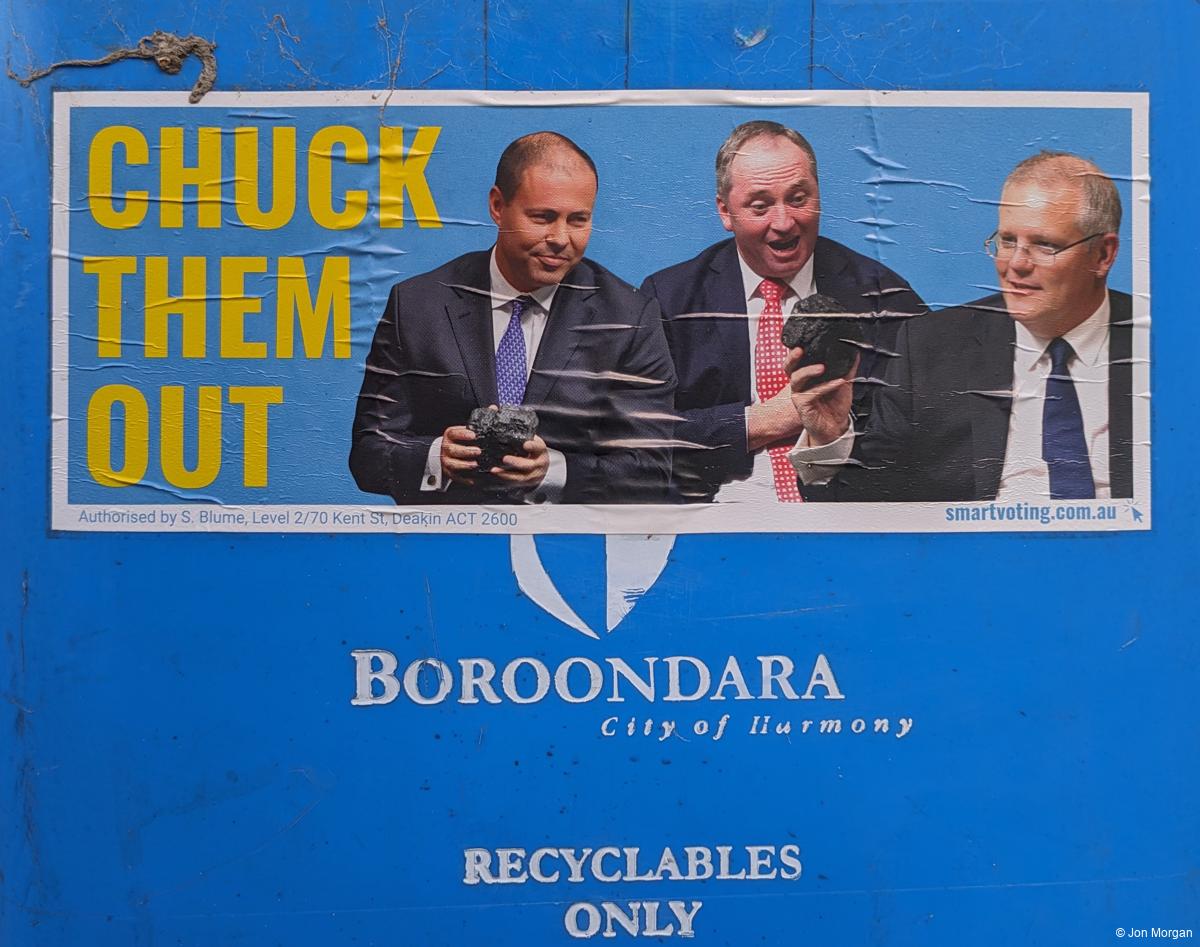

Chuck them out

As one example of their unpopularity, I would see this on my way to work:

For reference, from left to right we have:

- Josh Frydenberg: He was the Australian Treasurer (our second most powerful office) and also the local MP. He lost his seat to teal independent Monique Ryan, and has since retired from politics.

- Barnaby Joyce: He was the leader of the National party and Vice Prime Minister. He kept his seat but lost the party leadership.

- Scott Morrison: He was the Prime Minister, as well as the face of a much-disliked government. He was re-elected as MP, resigned as Liberal party leader after their election loss, and has since resigned as MP.

The election resulted in Labor winning a bare majority, before gaining an extra seat in a by-election. So it’s fair to say that “chucking them out” worked - while two of them were re-elected as MPs, their Coalition lost government and all three lost positions of leadership.

Josh Frydenberg’s fate was particularly notable: he had been widely expected to be the more moderate candidate for Liberal party leadership, and his failure to hold his seat made Peter Dutton’s eventual election as Opposition Leader a near certainty.

Considering two other nations

I’ve probably mentioned it somewhere, but there are three countries that I most closely follow the politics of:

-

Australia: I’ve lived here all my life. What’s more, after leaving Christadelphia I was actually able to vote here, so I needed to learn more about our politics.

-

UK: Our parent company is based in London. Changes in the UK government will affect us, as will other major events like Brexit (yes, I’ve written about that too).

-

US: At a personal level, this is probably the country where I have the most online friends. It’s also the largest economy in the world, and has been a key Australian ally since at least WW2. Major changes here will affect me, whether or not I have a vote in it (spoiler: I don’t).

Obviously each nation’s politics are different, but all three largely operate on a two party system. Our Liberal - National Coalition will be at least somewhat equivalent to the UK’s Conservative party and the US’s Republican party, while our Labor party is somewhat further to the left and more equivalent to the UK’s Labour Party and the US’s Democrat party.

They’ve each had their moment where the more conservative party was widely rejected by voters. In the case of the UK, it was July last year. Like in Australia, the UK Conservative party had been in government many years, had cycled through a number of Prime Ministers, and by the time the election came it felt like everyone was just waiting for it to be over.

The US had had their moment earlier: 4.5 years ago, to be precise. It was the time of Covid, which at least in Australia had initially improved the approval ratings of most leaders (including Morrison), no matter which party they came from. But the way Covid had been handled there felt like a big factor in Donald Trump’s eventual defeat by Joe Biden. During the campaign, Trump supporters could complain as much as they liked about Biden hiding away in his basement - but to me it seemed like an election winning strategy.

So, summing up, Albanese was not-Morrison, Starmer was not-Tory, and Biden was not-Trump. That’s not to say that each of those leaders (and their parties) didn’t have policies and plans and goals of their own. I’m quite sure they did, and some voters will have chosen to vote for them based on those policies. But it also felt like they benefited from not being the incumbent when things weren’t going well or their opponents had been in power too long.

One final factor: I think early on in all three governments there was a vibe of “now we’ve got the adults in the room”. They were going to be the responsible ones. That also meant an emphasis on the need to make tough decisions, I think particularly here and in the UK. Some of those tough decisions have been blamed on the excesses of the previous government - perhaps correctly - but that won’t save them if voters are upset with those decisions.

The magic words: Cost of living

Go back a few years, and the magic word here (and across the world) was “Covid”. Everything was Covid.

Nowadays the magic words seem to be “interest rates”, “inflation”, and the all-encompassing “cost of living”. There have also been significant issues with housing availability and affordability, which has lent itself to the ever-popular immigration scare.

I don’t pretend to be either a political pundit or an economist. But all the discussion about how to solve cost of living pressures seem to require politicians to square circles. Almost anything that might relieve cost of living issues is considered “inflationary”, and we’re told that inflationary spending will keep interest rates higher for longer and so make the cost of living crisis worse.

Voters cry out for cost of living relief, and politicians want to provide it (or at least to be seen to be providing it). Over the last couple of years, when Labor have talked about producing back to back surpluses as part of their “responsible management” to reduce inflation and bring down interest rates, I think the main response they’ve got from voters each time has been “If you’ve got all that money, why aren’t you doing more to help us with cost of living?!?!?” And yet politicians are also being told “If you give in to the cost of living demands you’ll just make everything worse”.

The global context

We do live in a global world, and at least some of the inflationary pressures and rush to raise interest rates (after historic lows…) has been global. And this is one of the things I notice from following the politics of multiple nations: Each nation seems to have many voters who think “Ignore that global context - you’re the government, you’re supposed to be fixing my problems. Why haven’t you?” And in a world where everyone’s experiencing it, the idea of a small country like Australia being able to buck the trend just doesn’t seem likely to me.

Right now many nations (including Australia) have seen inflation peak and then decline. Some have started reducing interest rates. And in February Australia got in on the act, and depending on economic conditions they may go down further in the coming months.

The Opposition has been quick to claim that Australia has done worse than other comparable economies. Perhaps they’re right - I’m not sure. And perhaps Australia under a Coalition government would have done better, or perhaps it would have done worse. But I find it hard to believe they could have avoided that global context, or that they will be able to avoid it if they return to government this election.

Considering the US election

I saw the cartoon I started with just days before the US election. In 2020 President Trump had seemed wildly unpopular and had lost the election, partly because things hadn’t been going so well and he was the incumbent. And yet, when 2024 came round it was the Democrats that were the incumbents, and Trump was returned to office.

Could that happen in Australia? It seems less likely than it did at the start of the year, but it still could.

The conventional wisdom is that incumbency is a benefit. And perhaps that’s often true. But when times aren’t so good, the current government can get the blame for it, whether or not they actually deserve it.

Sometimes there are moments where it feels like everybody wants the government changed. Here in Australia federally 2022 was one of those moments, as were 2013 and 2007 (the last two times government changed hands). In the US, the 2020 election felt like that. I didn’t get that feel in the 2024 election - but there was obviously enough dissatisfaction with the government to lead to change.

I don’t feel we’re at a “chuck Labor out” moment like we were at a “chuck Morrison out” moment. But there’s definitely dissatisfaction - will there be enough of it for the Coalition to win?

Are we better off now?

One reason I heard suggested for swinging voters in the US election was that voters will tend to ask themselves “Am I better off than under the previous government?” And many people answered that question with a rousing “No!”.

The Biden government and its supporters said that they delivered some economic growth, and that their policies for getting inflation and interest rates under control were working. But whether right or wrong, I gather it didn’t feel that way to many voters on the ground.

So far a Trump presidency has delivered more chaos than anything else, and I’m not convinced it’s going to magically improve the lives of the many who voted for him. But the fact remained: the Democrats were the incumbents, and that’s not such a comfortable position to be in when people are doing it tough.

Here in Australia, if the same question is asked, I’m not sure most voters would say that they feel better off now than they did in 2022. And that’s a potent attack line for the Coalition, which they’ve been constantly repeating. Sure, Labor and the Coalition can trade barbs over which side is the better economic manager, and which side contributed more to the current situation. But it doesn’t change the fact that while the Coalition were the incumbents three years ago, now Labor are the incumbents.

What does the government want to be remembered for?

I’m sure every government has things that they promised and wanted to achieve, as well as things that they actually did achieve and want to be remembered for.

Here’s some of the things I think Labor would like to have been remembered as:

- The party of responsible government.

- The party that brought integrity back to politics.

- The party that increased the minimum wage.

- The party that made the stage 3 tax cuts fairer, so that everyone got a tax cut, not just the wealthy.

- The party of the workers, and more generally of everyday Australians.

- The party who delivered a couple of unexpected surpluses after their predecessors had tried for years to achieve it.

- The party that ended the climate wars, moved away from fossil fuels to renewable energy, and started reducing Australia’s emissions.

- The party that saved the koala.

- The party that delivered the Voice referendum.

Some of them they didn’t achieve, most notably the Voice referendum - and I’m not sure about the koalas, either. Others probably aren’t remembered as much as they would like.

What might they actually be remembered for?

It seems what they will actually be remembered as, at least by many, could be quite different:

- The party that presided over a period of high inflation, and of interest rates that rose swiftly and then stayed high.

- The party that promised power prices would go down, then watched them go up.

- The party that threw open the door to a record number of immigrants, causing rent rises and difficulty finding accommodation.

- The party that presided over increased housing unaffordability.

- The party that made surpluses and refused to use them to help Australians struggling with cost of living.

- The party of out of touch elitists, wasting money on a failing Voice referendum when everyday Australians are doing it tough.

The first few are the ones that the Opposition most want to draw attention to.

Final pitches from the two parties

The election is on Saturday. Many have already voted.

Here’s the front page pitch from the Liberals:

Let’s get Australia Back on Track

Australians simply can’t afford another three years of Labor. At the next election, it will be time for a change. A change for the better – for you, your family and our country.

- Peter Dutton

And here’s the equivalent pitch from Labor:

Building Australia’s Future

The world has thrown a lot of tough challenges at Australia over the past few years.

Repairing an economy takes time but Australia is turning the corner.

It’s the same story as it has been the entire way: The challengers want to pin every failure on the government (and imply that we just have to give them the keys of the kingdom and they’ll easily fix those failures), while the incumbents have to acknowledge the difficulties, but then focus on the promised brighter future ahead. The Liberals then go on to talk about what they would do differently, while Labor focus on the things that they have achieved and what they plan to do if re-elected.

A new cartoon for a new election

I wanted to see how the cartoonist was handling this election. This one from February seemed most relevant.

That was a few months ago, when the Coalition were doing better in polls. What was the secret of their success? According to the cartoonist, it was that they were “Not the incumbent”.

This cartoon also feels accurate to me. And it’s certainly what most of their advertising has been focused on.

What about Canada’s election?

A few months ago, I saw a description of why the main opposition party in Canada was likely to win government at the upcoming election, and it sounded a lot like the discussion in Australia: Cost of living, inflation, difficulty finding housing, and high immigration numbers (see, it’s not just Australia!). Then along came Trump, everything changed, and the Liberals have won re-election under a new leader (though likely with a minority government).

It has to be said that Canada’s political environment is different from ours: They’re much more directly affected by the US, and Trump’s talk about them as the fifty-first state has not played well.

However, one thing that seems to have affected voter sentiment is their Conservative party leader being too similar to Trump. And in an Australian context that could apply to both Dutton as leader and to some of the Coalition party’s positions.

My prediction

I’ve said I’m not a political pundit. It’s still true. But I made my prediction three years ago, and haven’t seen a lot of reason to change it since. To me it seems most likely that Labor retain government, but it will be a minority government.

On the one hand, it had been a surprise Labor even reaching majority government last time. Given some of that was probably protest against the Morrison government, and given the difficult economic conditions, Labor losing seats this election wouldn’t be a surprise.

On the other hand, though, the Coalition were in a bad way after last election. It wasn’t just that they lost the election, but the way they lost. Not only did they lose enough seats to Labor for Labor to form government in their own right, but they’d also lost seats to the Greens and the teal independents, including seats that had been Coalition strongholds for decades.

To get back to government, the Coalition will either have to win back all those seats, or find other seats to replace them. And with the teal seats in particular, I’m not sure they’ve been able to address the voter concerns that led to the teals being elected in the first place. Perhaps cost of living concerns will be enough to capture other seats - but I wouldn’t count on it.

It would be foolish to say that the Coalition couldn’t win. There was a time, maybe late last year and early this year, where they seemed to be gaining enough momentum that I wondered if they could pull it off. But it feels like they’ve lost that momentum in the last couple of months.

The teal and Green seats are a new factor - I don’t think we’ll be able to tell how much of their support was protest and how much was a genuine voter shift till after the election. And even if the teals are re-elected, the Coalition could still gain enough seats from Labor that they’re the ones with a chance of forming minority government.

But if they do win, whether as a minority government or a majority government, it will probably be because they weren’t the incumbent in difficult times.