Favourite books for 2019

At the end of 2019 I had a list of books that made an impression on me that year, but never got round to writing them up. Since 2020 is now half over, it’s time to fix that.

I guarantee this list was completed December last year, and doesn’t contain any clever additions like Pandemic Preparedness for Dummies or The Traveller’s Guide to Cancelling Everything and Staying at Home.

I always find it difficult ordering lists of books, since different books are often good for very different reasons. However, I’ve tried as best as I can to put them in order of preference.

Non-fiction

1. Last Chance to See

I knew that Douglas Adams, author of the beloved Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (one of my 2017 picks) thought Last Chance to See was his best book, so I had intended to read it for a while. I also knew it had a section on New Zealand, so decided I had to read it before visiting there in February 2019.

And it was well worth it. It may be short, but it packs a real punch. And at the end of the year I decided that if there was one book I’d most recommend for the year, it was this one.

Douglas Adams positioned himself as the novice along for the ride:

[Mark Carwardine]’s role, essentially, was to be the one who knew what he was talking about. My role, and one for which I was entirely qualified, was to be an extremely ignorant non-zoologist to whom everything that happened would come as a complete surprise.

However, this wasn’t quite true. As well as being amusing, this book shows that he did understand evolutionary theory and why species are the way they are. Where I said re-reading HHGTTG made me better understand why Richard Dawkins liked Douglas Adams, reading this book made me better understand why Douglas Adams liked Richard Dawkins.

I mentioned New Zealand. Here’s his description of Fiordland:

If you took the whole of Norway, scrunched it up a bit, shook out all the moose and reindeer, hurled it ten thousand miles around the world and filled it with birds, then you’d be wasting your time, because it looks very much as if someone has already done it.

But then there’s this:

There is one sound, however, that we know we are not going to hear — not just because we have arrived at the wrong time of day, but because we have arrived in the wrong year. There will be no more right years.

Until 1987 Fiordland was the home of one of the strangest, most unearthly sounds in the world. For thousands of years, in the right season, the sound could be heard after nightfall throughout these wild peaks and valleys.

It was like a heartbeat: a deep powerful throb that echoed through the dark ravines. It was so deep that some people will tell you they felt it stirring in their gut before they could discern the actual sound, a sort of wump, a heavy wobble of air. Most people have never heard it at all, or ever will again. It was the sound of the kakapo, the old night parrot of New Zealand, sitting high on a rocky promontory and calling for a mate.

To me, that is a beautiful passage which gives a feeling of loss that can’t be conveyed by mere statistics.

And I think this is part of the wonder of this book: It can go from funny to sad to insightful within a paragraph or two. Even more so than HHGTTG. And that’s why a thirty year old non-fiction book became my must read book for the year: It’s a topic very close to my heart, and I’m not aware of anyone having written about it better than Douglas Adams.

Moving on from specific species, he reflected on humanity’s role in extinctions generally:

The system of life on this planet is so astoundingly complex that it was a long time before man even realised that it was a system at all and that it wasn’t something that was just there.

Up until that point [the extinction of the dodo] it hadn’t really clicked with man that an animal could just cease to exist. It was as if we hadn’t realised that if we kill something, it simply won’t be there any more. Ever. As a result of the extinction of the dodo we are sadder and wiser.

…

It’s easy to think that as a result of the extinction of the dodo we are now sadder and wiser, but there’s a lot of evidence to suggest that we are merely sadder and better informed.

…

Human beings, who are almost unique in having the ability to learn from the experience of others, are also remarkable for their apparent disinclination to do so.

There is also an afterword from Mark Carwardine, from which I particularly like this quote:

There is one last reason for caring, and I believe no other reason is necessary. It is certainly the reason why so many people have devoted their lives to protecting the likes of rhinos, parakeets, kakapos and dolphins. And it is simply this: the world would be a poorer, darker, lonelier place without them.

Overall, I think the book offers room for both optimism and pessimism. It shows how many individuals there are around the world dedicating their lives to try and preserve particular threatened species. However, it also shows that with the human species in our current state, preserving threatened animals is a difficult job, and you can never really be sure you’ve done enough.

Apparently Douglas and Mark talked over the years about doing a follow-up sometime. Those plans were cut short by Douglas Adams’ tragically early death, but 20 years after the original radio series the BBC got Stephen Fry to join Mark Carwardine for a TV series and book.

Since I’d enjoyed the first book so much, I read the second book and watched the TV series and would recommend both. The TV series in particular contained many beautiful moments and both Mark and Stephen clearly just liked being there.

That second series also showed reasons for both optimism and pessimism. Of the eight species Mark and Douglas had tried to find, only six remained in the wild. But for those six, Mark said he found the same people he and Douglas met 20 years ago: Still there, and still passionate about their cause.

2. Exactly: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World

A colleague describes Simon Winchester as able to make an interesting story about anything he puts his mind to. And it’s pretty true: Reading his books on the Oxford English Dictionary in Uni changed my view of the world forever. This book is about as far from those books as you can get, and yet it’s equally riveting.

This is the story of precision engineering, and how necessary precision was and is to so many things we take for granted nowadays. It deals with tolerances from 10-1 to 10-31, covering such topics as accurate navigation, mass-produced cars, jet engines, the Hubble telescope, and computer chips. It goes from precisions humans can measure and ensure to precisions that only automated processes can ensure.

In particular, I was fascinated by its focus on the importance of interchangeable parts. Maybe we take them for granted now, but there was a time when everything was individually made, which then required far more skill and effort to create or repair anything.

I think this was my favourite quote, showing the importance of precision to the mass produced items we take for granted:

The irony remains: a Rolls-Royce is so costly and exclusive and has enjoyed for so long a reputation of peerless creation and impeccable performance, but it does not require absolute precision at all stages of its making. A Model T Ford, however (or, indeed, any modern car, now made by robots rather than human beings, by Chaplinesque figures staring glassy-eyed at the endlessly flowing river of parts), requires precision as an absolute essential. Without it, the car doesn’t get made.

And yes, there was a discussion of which items are described as “the Rolls-Royce of” their respective industries. So maybe the book’s not so far away from the OED after all…

3. The Life & Death of Sherlock Holmes

When I was a teenager, I read all the Arthur Conan Doyle Sherlock Holmes stories. As I grew older, I also became interested in how much Sherlock Holmes had passed into the general culture. So this is a book I’ve been wanting to read for years: I just didn’t know it actually existed.

The book traces how the concept of Sherlock Holmes has grown, from Doyle’s original inspiration and early stories through to the BBC’s Sherlock. Along the way it touches on knock-offs and parodies, legal issues, financial issues, adaptations for film and radio, fan clubs, museums and exhibitions. And it’s not just England, either, or even just the English speaking world. Apparently Sherlock Holmes has been popular in Russia since shortly after Doyle published in his first story, and it continued to be popular in the USSR (including a highly regarded TV adaptation).

So, everyone knows what Sherlock Holmes is like. How much of the character comes from Doyle?

Elementary, my dear Watson.

It was through this spoken line that the phrase had been coined; in one way or another, its association with Holmes was attributable to William Gillette. The deerstalker had been placed on the detective’s head by the illustrator Sidney Paget and then taken on by Gillette and, in turn, the American illustrator Frederic Dorr Steele. The curved pipe was William Gillette’s idea, with the aim of making it easier to deliver his lines. William Gillette, then, had rather a lot to answer for in terms of the received image of Sherlock Holmes.

Conan Doyle himself could actually take credit only for the round magnifying glass, since Sherlock Holmes had carried just such a device in A Study in Scarlet. This was just as well, since Conan Doyle could be said to have had at least a finger, if not a whole hand, in shaping the myths surrounding his own character.

There have been many fascinating takes on the Sherlock Holmes story since Doyle finished with it, and the book gave me a list of other books I’d like to read, though I’m not sure I’ll ever get to them.

Take for example this description of Elementary, My Dear Watson (never actually filmed):

It started with Professor Moriarty in disguise - as Queen Victoria - at a Wild West show. There were numerous bizarre and close-call attempts by Moriarty to end the lives of Holmes and Watson. The plot involved Lenin and Trotsky, and in the final scene Moriarty attempted to escape to Russia in a hot-air balloon loaded with sacks of money.

It was the strangest Sherlock Holmes screenplay ever to have been written.

Finally, it did get me to watch the BBC’s Sherlock this year. And I really love it, both for the many references to the original ACD stories and for how it updated Sherlock Holmes to the modern era and explored his life, not just his cases.

4. Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

I found this a very thought-provoking book on Artificial Intelligence. The author believes AI has the potential to significantly change our world for both good and bad, and thus wants everyone to be able to contribute to the discussion of what we want AIs to achieve.

While it does talk about the near-term, specialised applications of AI I tend to hear discussed (self-driving cars, automated weapons, beating humans at Go, etc.), it also talks about the prospect of Artificial General Intelligence, of AI taking over from us, and of the very nature of life and what we might want the universe in the distant future to look like.

If you’re wondering about the title, by the author’s definition:

- Life 1.0 (biological stage): evolves its hardware and software

- Life 2.0 (cultural stage): evolves its hardware, designs much of its software

- Life 3.0 (technological stage): designs its hardware and software

Current-day humans are counted as Life 2.0 - on the software side we are able to learn and change our actions, but on the hardware side our potential is still largely constrained by our evolved bodies. Fully realised generalised AIs are expected to be able to change both their hardware and their software to suit their needs and goals.

5. Out of the Forest

This was the hardest book I read in 2019. It was Gregory Smith’s story of the many ways in which the system and society in general failed him, the few people who did support him, and how he was eventually able to come to terms with that and struggle to find his place in society (even ending up with a PhD in sociology).

And yeah, he also spent ten years living in the forest. This was obviously the hook that made the story unusual and able to be sold, but to me it wasn’t the most important part of the book.

Part of what made it difficult to read was his frank record of the many ways he sabotaged himself. Though it was clear that these couldn’t just be written off as personal failings: the system both contributed to that self-sabotage and exacerbated it.

Coming from a broken family, he spent 16 months in a Catholic orphanage. And as someone who grew up in a loving Christian family and as a child saw Christianity as a good thing, I was shocked by the things he experienced.

He received awful treatment from the nuns and from the other children at the orphanage, as well as from the brothers at the local Catholic school. However, it wasn’t just those institutions: The treatment was also backed up by the local police and the criminal justice system. I knew about some of these problems in the abstract, but stories like this show how much these things can affect a person’s life.

Thirty years later in the forest, the message he received in the orphanage was still lodged in his head: That he was a sinner. That he was broken. From only 16 months exposure to those teachings. That is appalling.

Then, after coming out of the forest and beginning his studies, he was able to put his experiences in a wider context. In particular, he learned about Forgotten Australians, the 2004 Senate report on people who had experienced institutional or out of home care as children:

Upwards of, and possibly more than 500 000 Australians experienced care in an orphanage, Home or other form of out-of-home care during the last century. As many of these people have had a family it is highly likely that every Australian either was, is related to, works with or knows someone who experienced childhood in an institution or out of home care environment.

And just that Executive Summary is chilling reading. As it states, this isn’t just past history, but affects our nation now and into the future.

For Gregory, reading it made him feel nausea but also relief - relief at finally understanding himself better. And it eventually put him on the path to his PhD, Nobody’s Children: An Exploration Into Adults Who Experienced Institutional Care, making him the leading academic in that area.

Like many forgotten Australians, he had had difficulty relating to people, and it was only in his belated university years that he was able to let more people into his life, better understand himself, and better find his place in the world. And so at the end he states:

My greatest ambition isn’t so much to chase the ball, it’s to simply enjoy my life and share what’s left of it with the people I love.

Fiction

1. The Discworld

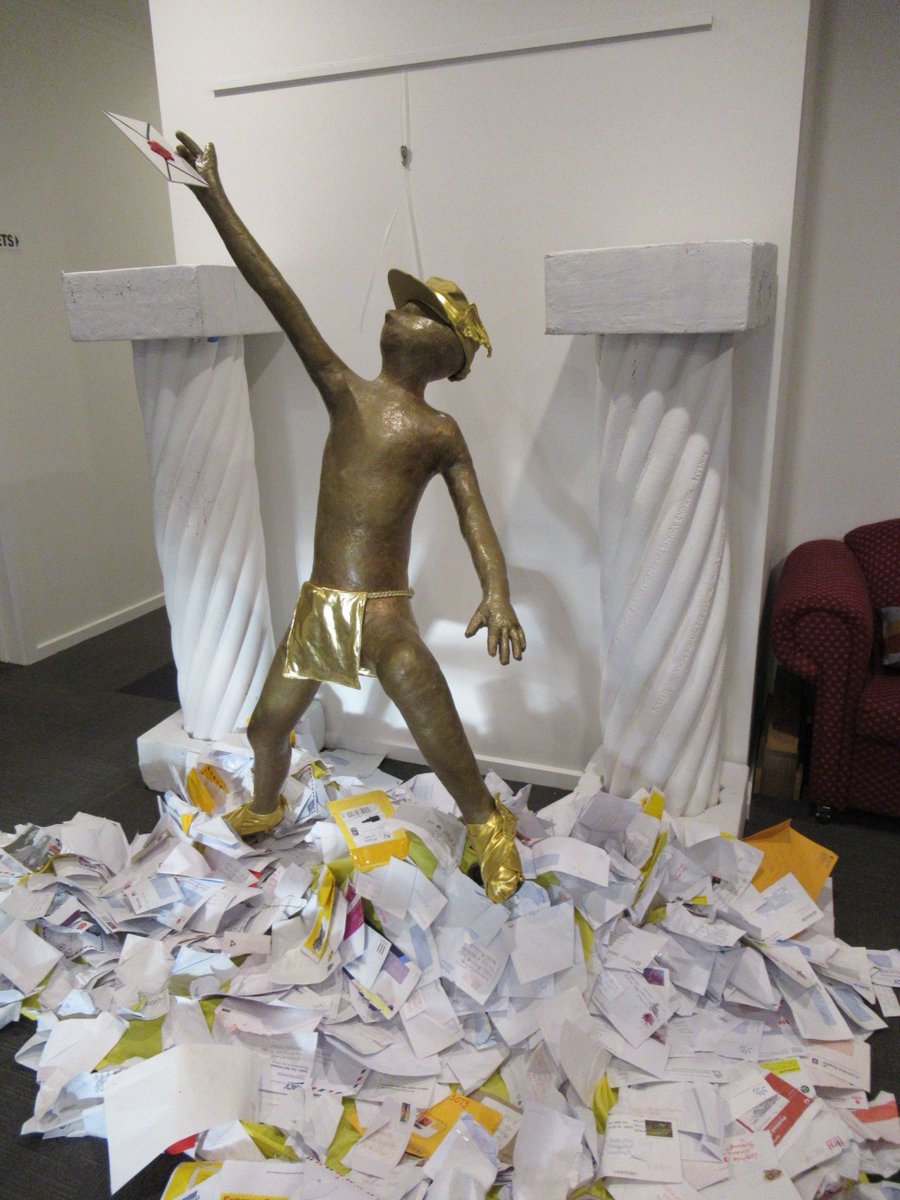

In the last few years I had read a couple of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels and knew they were good, but somehow never got to reading more. Then a community theatre near me put on the play Going Postal:

This is the first of three Industrial Revolution stories starring con-man Moist von Lipwig, and I enjoyed the play so much that I went on to read all three: Going Postal, Making Money, and Raising Steam. I’m pretty sure I laughed out loud more reading these books than any other books in 2019, and yet under the humorous situations and word-play there are many serious messages.

The books talk about human ingenuity, about the transformative effects of new technology, and about prejudice and racism. Since I came to these books late I had already picked up many of these messages from elsewhere (though maybe not written so well), but I’m sure there are people reading them in childhood who will first encounter some of these concepts through these books.

One of the most powerful threads in my reading and writing and thinking post-deconversion is recognising the importance of human ingenuity: Us solving our own problems rather than waiting around for a god to solve them for us. And I think Terry Pratchett describes this beautifully when talking about the clacks (his equivalent of the telegraph):

“What was magic, after all, but something that happened at the snap of a finger? Where was the magic in that? It was mumbled words and weird drawings in old books, and in the wrong hands it was as dangerous as hell, but not one half as dangerous as it could be in the right hands. The universe was full of the stuff; it made the stars stay up and the feet stay down.

But what was happening now … this was magical. Ordinary men had dreamed it up and put it together, building towers on rafts in swamps and across the frozen spines of mountains. They’d cursed and, worse, used logarithms. They’d waded through rivers and dabbled in trigonometry. They hadn’t dreamed, in the way people usually used the word, but they’d imagined a different world, and bent metal around it. And out of all the sweat and swearing and mathematics had come this … thing, dropping words across the world as softly as starlight.”

I’ve never read a bad Terry Pratchett book.

2. The Deathbird

Deathbird Stories: A Pantheon of Modern Gods by Harlan Ellison contains some interesting stories, but I really read it for one story: The Deathbird. And that story was amazing (it deservedly won the 1974 Hugo for Best Novelette). However, I wasn’t reading it because it was award-winning. I read it because I had heard that it was a new take on the story of Adam:

And for a farewell shot, a rewritten Genesis, advancing the theory that the snake was the good guy and, since God wrote the PR release, Old Snake simply got a lot of bad press.

I was particularly curious since I’d written my own take on the Adam story 6 months before (still unpublished - maybe one day…). As expected, it was very different and I loved it. Some chapters are made up of exam questions, while others appear completely disconnected, but it all builds up to an amazingly satisfying conclusion.

With hopefully little in the way of spoilers:

And Stack came back to Snake, who had served his function and protected Stack until Stack had learned that he was more powerful than the god he’d worshipped all through the history of Men. He came back to Snake and their hands touched and the bond of friendship was sealed at last, at the end.

And I still get goosebumps every time I read the final words:

The Deathbird closed its wings over the Earth until at last, at the end, there was only the great bird crouched over the dead cinder. Then the Deathbird raised its head to the star-filled sky and repeated the sigh of loss the Earth had felt at the end. Then its eyes closed, it tucked its head carefully under its wing, and all was night.

Far away, the stars waited for the cry of the Deathbird to reach them so final moments could be observed at last, at the end, for the race of Men.

3. The Dream-Quest of Vellitt-Boe

It shouldn’t be a surprise this book is on my list, since I already referenced it in God’s Bridge. I really like HP Lovecraft’s Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath, and when I heard this was the “feminist version” I wanted to read it.

From the author:

I must of course acknowledge Lovecraft’s The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath. I first read it at ten, thrilled and terrified, and uncomfortable with the racism but not yet aware that the total absence of women was also problematic. This story is my adult self returning to a thing I loved as a child and seeing whether I could make adult sense of it.

She uses the world Lovecraft created, but develops it much better than him, showing the unpredictable, shifting god-world that I wrote about in my post. Where the original took Lovecraft’s master dreamer (male, of course) from our world to the Dream World, this story took a woman from the Dream World to the Waking World.

In addition to the world-building, I particularly liked the cameo from Lovecraft’s master dreamer, showing an opinion of women’s roles that is hopefully less common now than it was in Lovecraft’s day:

“Women don’t dream large dreams”, he had said, dismissively. “It is all babies and housework. Tiny dreams.”

Because this is the thing: Vellitt-Boe did have larger dreams. She was a former far-traveller, and was able to go on her own quest for her own reasons. And, while she reflects that women were never anything but footnotes to men’s tales, in this story it is Lovecraft’s master dreamer who is the footnote in her tale.

I think (and hope) that women now have more freedom to make their own choices, dream their own dreams, and live their own lives.

When reading the book through the first time I found it deceptively short and simple, but by the end there was so much to unpack I needed to read it again. Basically, it was well-written, enjoyable, and changed my view of the world.

4. This Means War

I haven’t read much Harry Potter fan-fiction since I recommended a few in 2016. But This Means War quickly grabbed my attention.

Like most good fan-fiction I’ve seen, it takes important characteristics of canon Harry Potter and dials them up a notch. In this case, it’s particularly his loyalty to his friends and his strong sense of right and wrong:

I swear that, until my dying breath, I will fight for what is right, for those who can not fight for themselves, and I will do everything in my power to start us on the road to regaining the mysteries that we have lost.

Like canon Harry Potter, he is an outsider to the wizarding world who can see how much they have marginalised non-human magical creatures:

Every time I look around, I find allies that we have overlooked in the past. I find magnificence and glory that we, as humans, have tried to ignore and bury. I find goblins, I find dragons, I find werewolves, and I’ve not even started to look. How much have we missed out on, how much have we lost through our arrogance? How long will it take us to reclaim what we once had? How many of our children must grow up, being taught these lies, having our supposed seniority treated as fact?

He’s also a teenager experiencing a serious relationship for the first time, and so plans to finish the war with Voldemort quickly because it’s interfering with his love life.

There are many more beautiful passages, but I’ll just highlight this one:

With a lazy movement of her left wing, Gwyneth turned around and before them was the earth.

Harry stared down at the small blue planet, unable to think of a single word to say.

‘This is what you are fighting for,’ Gwyneth whispered in his mind. ‘If Voldemort wins, the blue will turn red and then black and we will leave and cross the great void. I have seen people like Voldemort throughout history, people who can only destroy, and it is our duty to help, it is everyone’s duty to stop him. We shall be there, youngling, and we will remind the world that everyone lives here together, and for one species to consider dominion over another intelligent species is abhorrent. This is our home, and has been for longer than your race has existed, and we hope it will continue to be so for as long as the planet exists.’

I find this similar to the vision of one beautiful but fragile world that our moon voyagers gave us.

5. Jane Eyre

Before reading this, I suspect my impressions came from an abridged version in my youth. I knew that it was a classic, that Mr Rochester had a mad wife, and that one of the key phrases is “reader, I married him”. But that was about it. I wasn’t looking forward to it, but had received strong enough recommendations that I decided to read it anyway.

What I found was that it was so much more than that. To me the centre of the story was not in the relationship between Jane and Mr Rochester, but in Jane’s search for happiness and purpose in an often hostile world. Others tried to tell her who she was or what she could do, with both religious and secular motivations, and from it all she found the person she wanted to be and chose to be.

6. Battlefield Earth

L Ron Hubbard was a Golden Age pulp sci-fi author before he founded Scientology, and this book was his attempt to get back into the sci-fi field 50 years after his first story.

In the year 3000, man has been declared an endangered species by the occupying aliens. Led by Jonnie Goodboy Tyler (aka “The MacTyler”), the book describes the improbably brilliant way humanity faces an escalating series of challenges from a hostile universe. It has a lot of what I enjoy about his short stories, but at much greater length. Not great literature, just a fun action story full of unexpected twists and turns (I saw it described as “brain candy”).

To me, some of the fun is in things that he probably didn’t intend to be humorous. Such as these quotes from his foreword:

To show that science fiction is not science fiction because of a particular kind of plot, this novel contains practically every type of story there is—detective, spy, adventure, western, love, air war, you name it. All except fantasy; there is none of that. The term “science” also includes economics and sociology and medicine where these are related to material things. So they’re in here, too.

…

And as an old pro I assure you that it is pure science fiction. No fantasy. Right on the rails of the genre. Science is for people. And so is science fiction.

I also find his jabs about areas like psychology, large government and taxes (“government theft”) amusing. But if I should happen to recommend Dianetics in 2020, remind me to check in with one of the psychologists he so much disliked.

7. Birthday

This is a transgender coming-of-age love story, written by a transgender author.

It’s the story of two boys, best friends, born on the same day. But one of them feels like they’re really supposed to be a girl, and can’t stand being a boy any more. It’s a story of change, of self-discovery, and of finding love, told through the events of six shared birthdays from ages 13 to 18.