Why lockdown doesn't work (as well as people expect)

This time last year, when Melbourne was in its second lockdown and case numbers were taking off, I heard a number of people asking why the numbers were still going up. The same is true of Sydney right now, which has been in lockdown for three weeks. People are scared and looking for someone to blame, and harmful narratives build.

So what exactly is a lockdown?

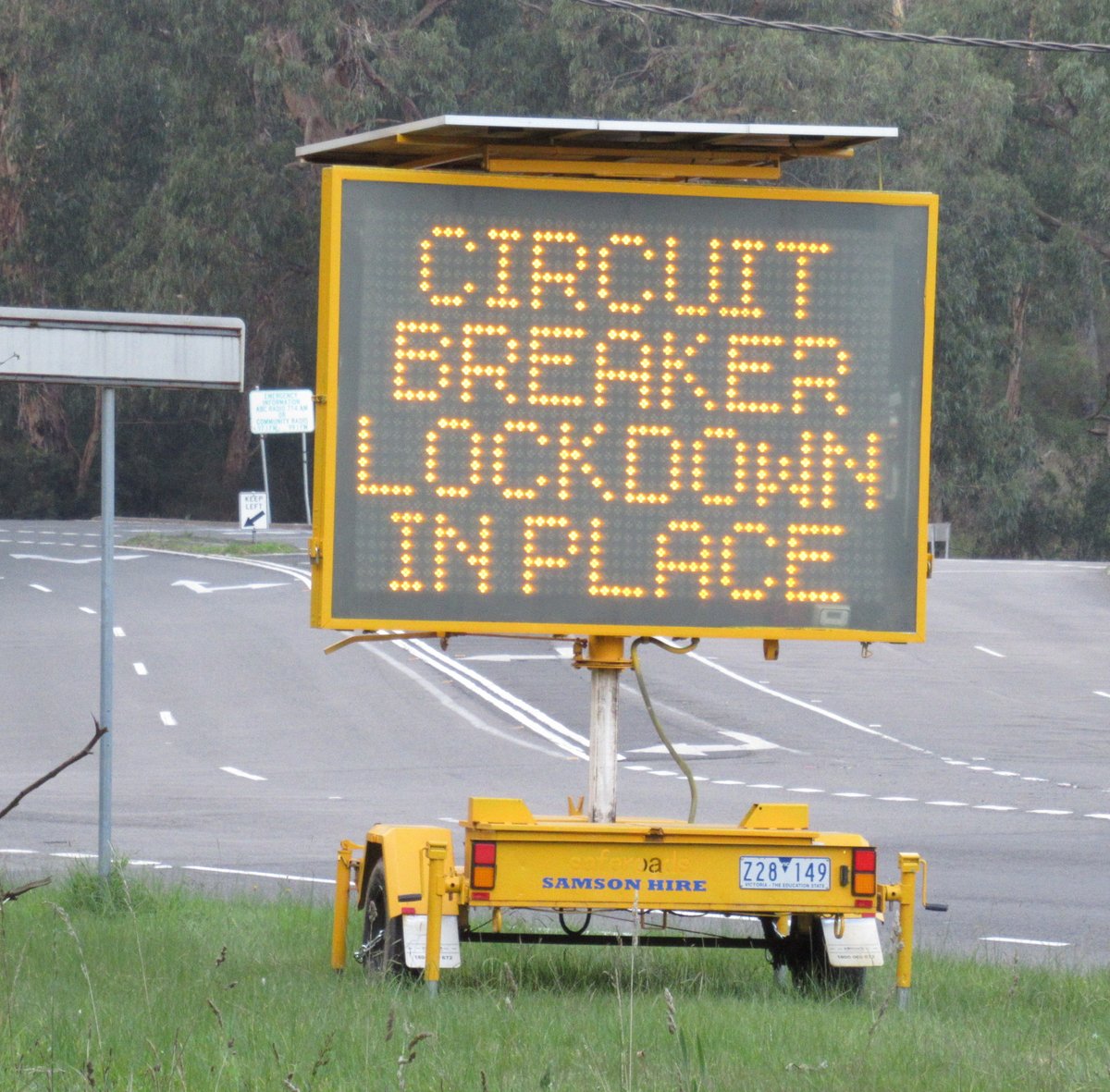

Lockdown is one of those words that came into the lexicon in 2020. It can now be put on a flashing sign and people are expected to know what it means:

However, different places round the world have had different restrictions. Melbourne’s long lockdown changed the rules many times, and other parts of Australia have drawn ideas from it without exactly copying it.

The main idea is simple: Significantly reduce contact between people so as to reduce transmission and ideally prevent exponential growth. In practice, that tended to go along with encouraging people to “stay home” and to avoid “non-essential activities”.

In Australia we’ve mostly limited it to four main reasons for leaving home (at least officially - there have usually been others as well). Take for example this list from NSW last week:

- Shopping for food or other essential goods and services

- Medical care or compassionate needs

- Exercise with no more than 2 people

- Essential work, or education, where you cannot work or study from home.

Yes, there has been different wording and slightly different restrictions in different states, but that has been the broad outline.

Lockdown leaves opportunities for transmission

I would say most of the people I heard talking about it were working from home and leaving their home for little more than the occasional grocery run. Given that, they couldn’t understand why numbers were still going up. Clearly, someone had to be doing something wrong.

However, the four reasons still provide a lot of opportunities for spread. In Melbourne last year, a lot of the transmission was happening in workplaces. That was explicitly a permitted activity. And, while much was made of people going to work with “symptoms”, Covid-19 is known to be infectious before symptoms manifest.

Similarly, much of Sydney’s spread in the last few weeks has been linked to workplaces, though Delta’s additional infectiousness seems to mean that those in the worker’s household are then more likely to catch the virus. That means that if they too work outside the home the spread can continue in a new workplace and reach more households. Perhaps they need to visit a grocery store or a food shop as well.

And all of this is completely legal, and often necessary.

Can’t we make restrictions tighter?

The short answer is that yes, we can. Melbourne did last year, bringing in the much talked of “Stage 4 restrictions” (though it’s not commonly remembered that they only took effect after our daily case numbers had peaked). Of them all, I suspect that reducing the types of retail which could operate and preventing other types of work from continuing had the biggest impact, because it reduced the potential for workplace transmission. However, it was also a highly invasive change.

A couple of weeks into lockdown, Sydney put a 10km ring on exercise and reduced outdoor gathering numbers from 10 to 2. Many have called for restrictions to retail and workplaces similar to what Melbourne did, and it sounds like they have actually done this today. They are also further tightening the rules on the worst affected Local Government Areas. Like with Melbourne, I suspect this will have a positive impact on case numbers, though it has a high cost.

In fact, it really needs financial support from government to make it work. Last year Victoria had federal support through JobKeeper (though it didn’t cover everyone), and I suspect one of the things limiting NSW from acting more decisively was the lack of such support (now available).

However, back to my point: Tightening the restrictions is helpful, but still won’t prevent all movement, and in fact will probably allow more than most people realise.

Take for example the much talked of aged care: Most of Victoria’s deaths last year were in aged care homes. There are ways to try and prevent serious consequences. Back then, it included things like requiring staff to use better protective equipment. This year it includes vaccinating residents and staff alike. What we can’t do is to tell all those aged care workers to just do the right thing and stay home - otherwise the residents will be left without necessary care.

And the same is true for many other parts of society: We can try and mitigate the risk of spread, but we can’t completely shut them down. So while there is significant community transmission those areas will continue to have potential for spread, lockdown or no lockdown.

What do you mean by lockdown “working”?

I think the real problem is deciding what is meant by “working”. Many seem to expect lockdown to achieve more than it is actually able to.

The lockdown is almost certainly reducing transmission, and thus cutting the speed of growth. Even where there is, say, workplace transmission, the limitations on visitors to the home and on larger gatherings may mean a positive case only infects immediate family, not a wider group of friends and family and the general public.

However, it doesn’t magically fix the problem in a day or a week. We saw that in Melbourne last year. We saw it in other parts of the world. And now we’re seeing it in Sydney.

If each person continues to infect more than one person in spite of lockdown, daily numbers will continue to grow - just not as fast as they would have without lockdown. And even if it gets to the stage where, on average, positive cases infect less than one person, daily case numbers will still take time to come down.

Have you considered the time lag?

That leads on to other questions I’ve seen: We called lockdown two days ago. Why are case numbers going up? And why are there so many new exposure sites from people testing positive in lockdown?

People who are reported positive today were probably tested yesterday, or perhaps the day before. In many cases they won’t have been tested till some time after showing symptoms, and a typical time quoted for showing symptoms is 5 days after initial infection. So it wouldn’t be a surprise if they acquired the infection a week or even two weeks ago. Declaring a lockdown can’t do anything about infections acquired before the start of the lockdown.

Just because people want quick answers doesn’t mean they exist.

Incidentally, this is one of the reasons why I’m skeptical of the trendy 3 - 5 day snap lockdowns used by the likes of Adelaide, Brisbane, and Perth, and right now Melbourne. Yes, they may well reduce chains of transmission and stop the situation growing out of control, which was the reason given for our current lockdown. However, it’s not really long enough to be confident lockdown has “worked”, and so I suspect if it “succeeds” there’s a fair chance that the lockdown was never needed and should never have been called.

In our case, we’re two days in and have had cases both days. I’d be surprised if they can have the confidence to end it in the planned five days. But even if we had no cases for the remaining three days there could still be a positive test on day 6 from someone who caught it before lockdown started.

Would lockdown have “worked” then? Maybe, if it stopped them from spreading it to others. But maybe not.

Have you considered luck?

Particularly early on in an outbreak, one super-spreader event can have a bigger effect on overall numbers than steady daily growth. The jurisdiction with overall tighter controls but one super-spreader event from a permitted activity may do worse than the jurisdiction which took longer to act and had looser restrictions but got lucky and avoided super-spreaders. Similarly, a jurisdiction that claims its success has to do with its tight controls and decisive action may be completely wrong - they may just have got lucky.

It’s before lockdown, but consider Melbourne’s current outbreak. It’s believed to have two sources: One led to a cluster of 4 cases so far and seems relatively contained, the other has spread via sporting matches, family gatherings, pubs, and schools to places as far flung as Phillip Island and Bacchus Marsh, and is the reason for lockdown. Both the same strain of the virus, both with the same public health settings in place, but completely different outcomes. If the second infection had been somewhere else both clusters might have been small, and thus easily contained without lockdown.

However, it’s not complete luck, particularly as case numbers grow and as lockdown lasts. I remember hearing people complaining about how often the people testing positive had a lot of exposure sites, but in reality that’s what you would expect. People with more activity are more likely to be in a position both to catch Covid and to pass it on.

Still room for contact tracing

It seems to me that too often in this pandemic people expect one measure to work and work perfectly. This has meant, for example, people viewing contact tracing and lockdown as opposite strategies, and that going into lockdown means contact tracing has failed.

I get it: I’d prefer contact tracing to be able to prevent a lockdown too. However, the last couple of times Melbourne has gone into lockdown it seems to me contact tracing has worked fairly quickly to discover the extent of the problem (which is why lockdown was called). Maybe it could have handled the problem without lockdown, maybe it couldn’t, but it hasn’t stopped working just because lockdown was called.

Lockdown is a blunt instrument. It significantly restricts the movement of a large number of people, most of whom will not have Covid. But there are still people who unknowingly have Covid, and lockdown may not restrict their movement as much as we might like.

This is where contact tracing can come into its own, particularly early in an outbreak where there aren’t many positive cases. By finding the people who may have come into contact with that person, we can discover people at a higher risk of catching and spreading Covid. That means we can require them to take a Covid test. We can require them to isolate for a period of time, typically 14 days. We can also isolate contacts-of-contacts, knowing they too are at higher risk.

What this means is that it’s much more likely that if those people do test positive they have been in isolation for the entire infectious period. That makes certain it doesn’t get a chance to spread in the workplace, or at the grocery store, or during any of the other activities permitted during lockdown.

I suspect it also shortens the time lag mentioned above. It increases the chance that close contacts who did catch it are tested and test positive before they show symptoms (though it may also mean testing them too soon, which is why we have frequently required even those who tested negative to isolate the full fourteen days).

Just “doing the right thing” is not enough

This is the main reason why I think we need to be realistic about what lockdown can and can’t achieve. It’s far too common for politicians and individuals alike to assume the main reason it’s “not working” is that people are breaking the rules. As far as I can tell, that’s just not true, and can lead to stigmatising those who catch it while doing the “right thing”.

We need to be able to have the nuanced conversation that says “The rules are there for a reason, and it’s probably a good idea to follow them - but rulebreakers aren’t the main cause of spread, and doing ‘the right thing’ doesn’t magically fix everything”.

I gather Sydney has had at least one non-permitted party during lockdown which caused additional spread. It would be better if that party hadn’t happened. But I think politicians can then focus on those particular wrongdoings, and thus end up putting blame on individuals rather than questioning whether there are systemic issues with the lockdown restrictions that need addressing.

The reality is that, whether in lockdown or not, many people will do “the right thing” and still catch Covid. Many others will do “the wrong thing” and not catch Covid. That may not be “fair”, but it’s the way the world works.

Conclusion

I’m writing this from lockdown right now, and I’d certainly prefer a world without lockdowns. It’s understandable that people in a long lockdown get frustrated it doesn’t work as well as hoped.

Lockdown does achieve things, but it’s not magic. It’s about reducing movement, but not all movement is created equal, and lockdown doesn’t restrict the movement of some people as much as others anyway. That shouldn’t be an excuse to target people perceived to be doing the wrong thing.

Note of course that I am not an epidemiologist, and this is all my personal opinion and observation.