Covid diary: Growing awareness

Covid-19 has completely changed our world, and we don’t know how long the disruptions will last or what will come next. When people talk about living during a “historic moment”, this is what they’re talking about.

So I wanted to record some of my personal impressions, starting from the time when the novel coronavirus felt like a distant problem affecting other people, not something which would change my life.

A new decade begins

Covid-19 was first reported to the World Health Organisation on 31 December 2019 (that’s where the “19” in the name comes from). It was near the end of my company’s mandatory break between Christmas and New Year, and I was more interested in reflecting bridges than in the start of a pandemic that would dramatically reshape our world.

That evening I was trying desperately to finish my planned post on the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing (a task which would actually take me through the night almost to sunrise).

At the same time, I was also pondering the start of a new year and a new decade, and how much my life had changed over the past decade. I even found myself writing poetry. The dread disease was already in the world, straining at the leash, and none of us knew.

I had big plans for 2020, and none of them included being confined to my house. In fact, I intended to travel round the world, with places like Israel, Italy, Switzerland, and the US on my itinerary. They weren’t new plans, either: They really started when I visited the UK and Switzerland in 2016.

When reflecting on the 2010s, I wrote this:

I don’t expect the 2020s will be perfect. There are sure to be many sorrows, both for me personally and for the world generally. I don’t know what will come next, and I can’t control it or stop it.

And all I intended was a general observation that we’re not completely in control and unexpected things happen. I didn’t realise how quickly Covid-19 would step in and steal the show.

Later that day I went for my first hike for the decade. I walked in my local Dandenong Ranges, and saw my first wallaby, first echidna, first rosella, and first sunset for the new decade. It really felt like a continuation of the new life I’d built for myself in the final years of the previous decade, and I was feeling positive about the future.

The only really unusual thing was the sunset:

However, this sunset was not a sign of the impending Covid-19 pandemic, but a continuation of one of Australia’s worst bushfire seasons on record.

The bushfire crisis

In the 2019 spring / summer season vast areas had been burnt across NSW and Queensland. From one attempt I saw to put it in perspective in January:

Australia’s wildfires have dwarfed other catastrophic blazes, with its burnt terrain more than twice the extent of that ravaged this year by fires in Brazil, California and Indonesia combined.

As we were at the start of a new decade, this was something of a wake up call: We had been told this was the decade we were being told we had to get on top of carbon emissions. The changing climate was already affecting us, and if we didn’t act it could get a lot worse.

In the final week of 2019 large fires began in Victoria, particularly in the far east. There were some truly apocalyptic looking photos being shared online. And quite a few of the fires were in areas I’d visited and knew, and I had friends who were affected by some of them. Things were bad.

In the last few months we’ve grown used to news of unusually clear skies and pure air as a result of Covid-19 related shutdowns. However, it’s worth remembering that in early January Sydney had been under a pall of smoke for a month, while Canberra started the year with the worst air quality readings in the world. In my area, smoke from the Victorian fires brought us low visibility and sunsets that could be both spectacular and unusual.

One day, walking home from the station, I saw the sun sinking blood red, but when it neared the horizon it was so pale it looked more like the moon at total eclipse.

From the train station near work I can usually see clear to the city centre, but the following morning I could hardly see the cranes next to my workplace a kilometre away.

At the time there was talk of the Victorian fires burning for months. As it was, there were heavy rains at intervals throughout January and I think all of the fires were put out or at least under control by the end of the month. But there had been significant damage to many areas, and I think we expected it to be the biggest disaster of the year. Many of the areas affected were tourist areas, and so we knew there would be a need for people to visit and support them.

And I do now wonder how much the bushfires affected our response to Covid-19. Did we have disaster fatigue? Did we feel it was too soon for another crisis? We were already talking about the recession potential from the bushfires, and I wonder whether that played on the minds of officials having to make tough decisions to fight the virus.

A Melbourne summer

So there we are - middle of January, Melbourne under a cloud of smoke, and Covid-19 had already begun to spread through the world. And yet life continued on fairly normally.

The State Library had the Ashes on loan. I’d already seen them at Lord’s in 2016, but it was too good an opportunity to miss. So one Saturday I went in on a crowded train and visited the display.

As it was a beautiful summer evening, I also took the chance to see an outdoor production of Hamlet at the Botanic Gardens:

Hamlet had been one of my Year 12 set texts and his indecisiveness had really appealed to me. It may have been fifteen years on, but I still enjoyed the play.

Later that month the Australian Open was on, and we had large numbers of players and spectators coming from abroad. At the time there was no concern about them bringing disease with them. The real concern was whether the air quality would risk the athletes’ health.

The lockdowns and border closures begin

I don’t know when I started hearing about a new (“novel”) coronavirus (it wasn’t yet called Covid-19). Perhaps it was from the news, or maybe I heard about it from one of my co-workers originally from China.

Anyway, China imposed a tight lock-down on the worst affected province. At the time there had also been some spread in both South Korea and Iran. However, I don’t think confirmed case numbers were that high in most other countries, so I’m sure I wondered whether China were over-reacting. I also didn’t think any Western democracy would accept significant lockdowns.

By the start of February, Australia had joined a number of other countries in closing the border to people who had travelled through China. We had confirmed our first case. And as far as disease control went, there were some generic recommendations: Make sure you wash your hands, don’t touch your face, make sure you stay home if you feel sick.

But the worries I was hearing weren’t so much about community spread within Australia as the economic consequences. Many universities relied on Chinese students who might not be able to make start of semester, and tourist hot-spots like the Great Ocean Road relied on Chinese tourists. A lot of Chinese manufacturing was shut down, which could affect both demand for Australian raw materials and supplies of consumer goods.

The summer continues

And what was I doing? At the start of February I admired the crashing waves at Flinders and Cape Schanck, camped at Sorrento, then took the ferry to Queenscliff for the day.

I wasn’t to know that in a couple of months beaches would be closed, and when we talked about waves it would be pandemic waves.

The next weekend I climbed Mount Donna Buang (with more than 1 km elevation change). A few years ago that was the first place I saw snow in Australia. I’d sworn that one day I’d come back in summer, and this seemed as good a time as any.

The evenings were long, so sometimes I went walking by the Yarra after work:

I also met and held a friend’s young baby while discussing moral philosophy at length with said friend. It was quite possibly the first baby I’d held since my own younger siblings. Life was proceeding as normal, and the words “social distancing” hadn’t yet entered our shared vocabulary.

Going cruising

In February we were starting to hear about the dangers of cruise ships as Covid-19 incubators, particularly given the saga of the Diamond Princess. Also in February, I went on 3 different cruises, at least one of them after hearing about the Diamond Princess, and didn’t even notice the irony till now. Of course, there’s a big difference between an international cruise holiday and spending part of a day in the Greater Melbourne area in contact with other Melburnians.

So what was there? There was the ferry from Sorrento to Queenscliff I’ve already mentioned, a “swim with dolphins and seals” cruise also starting from Sorrento, and a spaceship themed night cruise starting from the city. I certainly hadn’t planned for them to all be in the same month - it just kind of happened.

The wildlife cruise saw me fighting terrible traffic and crazy parking conditions, and left me sunburnt and with a blood-stained beard. It also saw me discover that occasional swimming lessons as a child in a calm indoor pool weren’t adequate for facing windy conditions and heavy waves. Which in its turn even inspired me to start going to a local swimming pool for practice - well, until Covid-19 shut all the pools down, anyway.

However, I also discovered (as I hoped) that swimming within a few metres of a seal is cool. So is watching them dive or swim lazily along near the boat.

Seeing a ray on the ocean floor a few metres below you and blissfully unconcerned is cool. Watching a pod of dolphins leaping out of the sea or come closer to investigate the boat is cool. A fall that loosens your teeth, makes it difficult to eat, and leaves scars is not cool.

The night cruise the following weekend was something entirely different. Probably closer in atmosphere to a floating night-club (venues also considered a Covid-19 risk…).

I didn’t want to dress up, but did take the chance to wear temporary tattoos for the first time. The tattoos may not have been space-related, but I’m told the eagles I chose looked like the Apollo 11 mission patch. The fact that the one with a blue background from a distance looked more like a bruise was merely an unfortunate detail.

Starting to affect me

In the background, I’d been trying to finalise my travel itinerary. By the end of January travel was starting to become a little uncertain, and it wasn’t clear how much travel insurance would cover, but I didn’t have any particular concerns about my travel being disrupted.

I’ve talked about cruise ships, but I did notice that people had caught Covid-19 in flight from fellow passengers. However, I don’t think that risk bothered me as much as perhaps it should have. After all, there was no way to get where I wanted to be without a few flights, so that was just a risk I would have to take.

In the middle of February, I got the first travel notification that directly affected my plans: Israel was closing its borders to people transiting through Singapore. At the time, I didn’t worry too much: I decided to wait to finalise my plans, but thought if necessary I could go straight through to Israel without staying for a few days in Singapore.

And I really don’t know what I was thinking then: Maybe I was in denial. After all, July was still months away, and perhaps it would all be under control by then. Or maybe I thought it was unstoppable and under-estimated its seriousness. After all, at some point I saw predictions that it would end up infecting at least a third of the world’s population. If it truly did take over the world, I expected that travel bans would have to be dropped: If it were sufficiently contagious it would continue to spread within each country no matter what happened at the borders. And I knew WHO had spoken against the travel bans.

I was still keeping a close eye on case numbers, and the largest growth remained in China. I probably hoped that the disease was contained - maybe China had overreacted? Or maybe they’d caught it just in time?

So for me, the decisive shock was the northern Italy shutdown near the end of February. It started with a few towns, then spread to more towns, to all northern Italy, and then to all Italy.

It wasn’t just that I was planning to be in Italy in July: This showed that the disease wasn’t contained, that a Western nation could and did impose strict lockdown, and that harsh measures were actually necessary to control the disease. Pretty soon, borders closed across Europe to try and prevent the spread, but it was too late. Italy may have led the way, but we saw case numbers rise in France, in Germany, in the UK, in Spain, and in so many other places. We started to hear stories of ICUs being overwhelmed. Of people unable to get the ventilators they needed and left to live or die.

I’m sure it was after that that I began to see the calls to cancel everything and lockdown, preferably yesterday. Even then it took time for me to be convinced. After all, there was no prospect of a vaccine for 12 - 18 months (and even that was only if we were lucky). Were we really going to be cancelling everything for more than a year? Or were we just delaying the inevitable?

Family travels

At the start of March, much of my family was overseas for a family event. Given my later travel plans, I hadn’t been able to join them. Some of them were due to stay overseas long-term, while the rest were going to return in a couple of weeks - certainly by the end of the month.

I don’t recall any discussion in February about whether that travel was a good idea. The plans had all been made, the tickets were booked, and travel conditions seemed reasonable enough.

As it turned out, if the event had been even a week later things could have been very different. We weren’t to know that some of them would come back with symptoms (though they tested negative), that some of the flights booked would be rescheduled or simply cancelled, and that a mandatory 14 day quarantine period would soon be introduced for returning travellers.

Still not avoiding crowds

So there I was still in Australia approaching the start of March. It was a leap year and 29 February was a Saturday, so I took the opportunity to admire the music of Sir Arthur Sullivan, celebrate Frederic’s birthday, and write clickbait disproving God. The Sullivan event had maybe 50 - 100 people - who could possibly worry about such small crowd sizes?

The following day was the Knox Festival. I don’t know what the crowd numbers were like, but there were lots of people. I knew parking would be in short supply, so I walked there (maybe I should have tried a unicycle instead?)

The following weekend, International Women’s Day found me at the Women’s T20 World Cup final with a record-breaking crowd. I was a little uneasy about whether large crowds were a good idea, but wasn’t to know that a mere two weeks later I’d be writing in bewilderment about how much had changed since then.

In fact, that final could well turn out to be the largest event at the MCG this year: It seems unlikely that the AFL Grand Final will be able to have a large crowd, while the Men’s T20 World Cup will probably have to be postponed or cancelled.

Within days the WHO had officially declared Covid-19 a pandemic. I was registered to attend other public events in the next few weeks, and wasn’t sure whether I should attend or not. However, as concerns around public gatherings grew the decision was taken out of my hands as one event after another was cancelled.

Sporting cancellations

The day after the World Cup final I heard that the next major tennis tournament, in California, had been cancelled. There was no immediate decision on the subsequent tournament in Florida, but we expected that would be cancelled too. After that, the tour was due to head to Europe, but it seemed unlikely that those tournaments would go ahead. In particular, given Italy had just gone into country-wide lockdown, it was hard to see a major tournament in Rome in May.

Later that week our men’s cricket team was due to begin a three match series against NZ. Unlike the record-breaking World Cup final, this would be played without crowds. However, as it turned out NZ was going into lockdown, and so the final two matches were cancelled to allow their team to return to NZ before the start of mandatory quarantine.

Even the Olympics - scheduled for Japan later in the year - were coming into question. It seemed like no-one wanted to be responsible for actually cancelling them, but as the situation deteriorated worldwide it was hard to see them going ahead.

In Melbourne, the big debate was around the Grand Prix the following weekend. It was due to have even bigger crowds than the World Cup final, which could lead to disastrous spread. Some of the teams were actually from Italy, and team members were showing symptoms and being tested for Covid-19. However, like with the Olympics, it seemed like there could be serious economic consequences and no-one wanted to be responsible for actually cancelling it until the last minute. There had been earlier bans on travellers from Iran and South Korea, and many speculated that the government waited till the Grand Prix teams had arrived before adding Italy to the list.

Panic buying

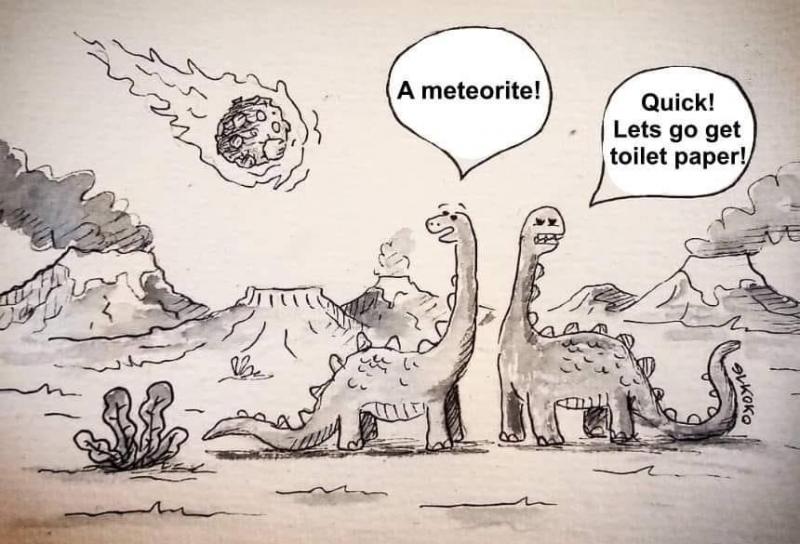

One other sign things weren’t normal was the panic buying. It all began with toilet paper. We hadn’t realised that all major disasters involve a run on toilet paper:

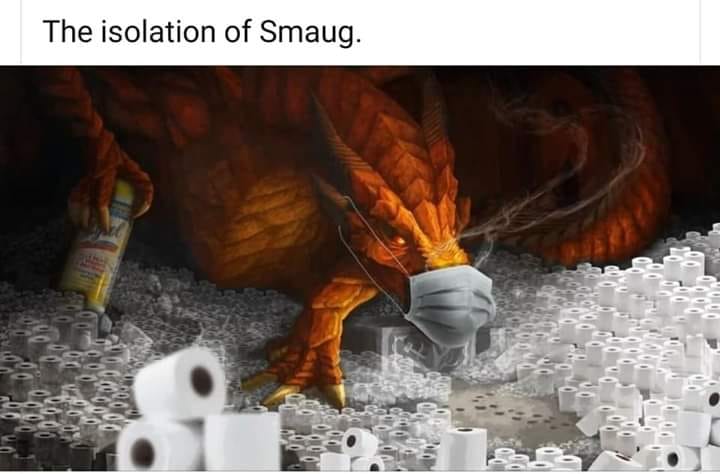

Nor did we know that hoarding could go far beyond mere gold:

However, it did seem a little odd focusing on toilet paper to the exclusion of other useful supplies. As Thorin Oakenshield himself almost said, if more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded toilet paper, it would be a merrier world.

Fortunately, people quickly realised this: Seeing the shelves bare of toilet paper, paper towel, and hand sanitiser, they began panic buying things like pasta, canned foods, bread, and flour.

Personally, I stayed out of it. I was surprised to hear of the panic buying, but since I wasn’t in pressing need of groceries I preferred just to stay away and give everyone else a chance to come to their senses.

Could I have caught it?

At work, in the room I was in we basically had a daily coronavirus meeting. Nothing formal, but discussion would start with a couple of people and end up sucking everyone in.

What were we talking about? The latest case numbers, where in Melbourne might be more or less safe, the latest wild theories, whether we’d close schools, and whether people would be willing to eat out at a Chinese restaurant or hoard toilet paper. I most commonly said things like “No-one really knows enough about this disease to be sure about that”.

Anyway, the Thursday after the World Cup final one of them informed me it was on the news there had been a Covid-19 case there. Given how many people had been at the final, I didn’t think I was likely to have come into close contact with anyone having the disease, but was still glad to find the known case was on the opposite side of the stadium.

And it was maybe five minutes after that I started to feel sick. I assumed it was all in the mind, but it didn’t get much better the rest of the day. I said jokingly to co-workers that if they didn’t see me next day I must have got Covid-19.

By evening I had a fever, and the next day I stayed home sick. In spite of my joke, I didn’t think it was likely to be Covid-19: I didn’t know where I could have got it, it didn’t seem very severe, and the other symptoms didn’t really match what we knew of Covid-19. I did wonder whether I should get tested, but there were tight restrictions on the tests and I wouldn’t have qualified. I also saw pictures of a lengthy queue at one testing station, and was concerned it might actually be a good place to catch Covid-19.

The same day I was home sick the Australian government issued a warning encouraging Australians to reconsider their need to travel anywhere in the world. Shortly afterwards, it was escalated to Do Not Travel, and citizens were encouraged to return home as soon as possible. Not only was there a risk of catching the disease while travelling, but border restrictions and flight availability were changing rapidly. This left me with family members and friends overseas to worry about, while my own travel plans were looking increasingly uncertain (I was glad I’d held off from finalising plans and buying tickets).

That was 2.5 months ago, and I haven’t been back to the office since. I worked from home the following week because I still wasn’t 100% and didn’t want to spread anything. And the week after that our entire workforce transitioned to working from home.

The week it all came home to me

I think I already knew about Covid-19’s seriousness in the abstract, but was in denial about how much it could affect me personally. That was how I could be part of a record crowd at the MCG despite knowing that large crowds increased the risk of spread. And it was the week after that final when it really came home to me how much Covid-19 could change my way of life.

It showed that the disease could disrupt the sports I followed. It could cancel the events I loved, and make mass gatherings a thing of the past for the foreseeable future. It could stop me travelling the world.

But it wasn’t just about travel: Melbourne didn’t yet have a huge number of cases, but it could affect Melbourne, and it could affect me. It could make me the one responsible for catching it and then passing it on to co-workers and family members. It could even confine me to my home.

I’ve been in a fairly privileged position for some years. If there have been things I wanted enough, I could usually get them or do them. However, this time it was different: It didn’t matter how carefully I’d planned, or how hard I’d worked, or whether I’d been a good person or not. The disease didn’t care, and the public response was going to go to greater lengths than I had thought possible to try and control the disease.

Conclusion

In the first 2.5 months of 2020 I went from having never heard of coronaviruses to recognising that the novel coronavirus Covid-19 could completely disrupt my plans and change my way of life. Cue an ironic joke about 20:20 hindsight.

There has been a lot of talk about how officials around the world mishandled the Covid-19 response, particularly in reacting too slowly. And some of that may be true.

However, it was a difficult and rapidly changing situation, and I can see looking at my own response how frequently I under-estimated the disease. Even when I knew it was serious I was in denial about how much we would need to change to fight it, and how much it could affect me. And I’m sure even those wanting more rapid action must have realised that serious restrictions couldn’t be imposed from above without some level of public buy-in and acceptance.

So where does this leave me? It leaves me writing about Covid-19, for a start: Everything I’ve posted on my blog since March has been somehow related to Covid-19.

As far as travel goes, I was meant to have left Australia in just over a month. I’ve definitely cancelled those plans. For now I’ve retained the option to travel in September, but would be surprised if it actually works out. And yes, that’s disappointing.

However, once it became clear to me how serious the pandemic was, I became more concerned about the many people who would be affected: Colleagues and friends in England, friends across the US, those in poorer health, and those with less safety net than me to deal with the associated economic downturn. My plans were important to me, but if the worst thing that happens to me this year is missing out on travel opportunities I’ll have done pretty well.

This has all moved so quickly: It was probably less than a couple of months between when I thought no Western nation would accept lock-downs and when I was under lock-down myself.

And so for my next post I intend to write about some of my experiences under lock-down. Australia has been easing restrictions for the last few weeks, and I don’t want to forget what it was really like.